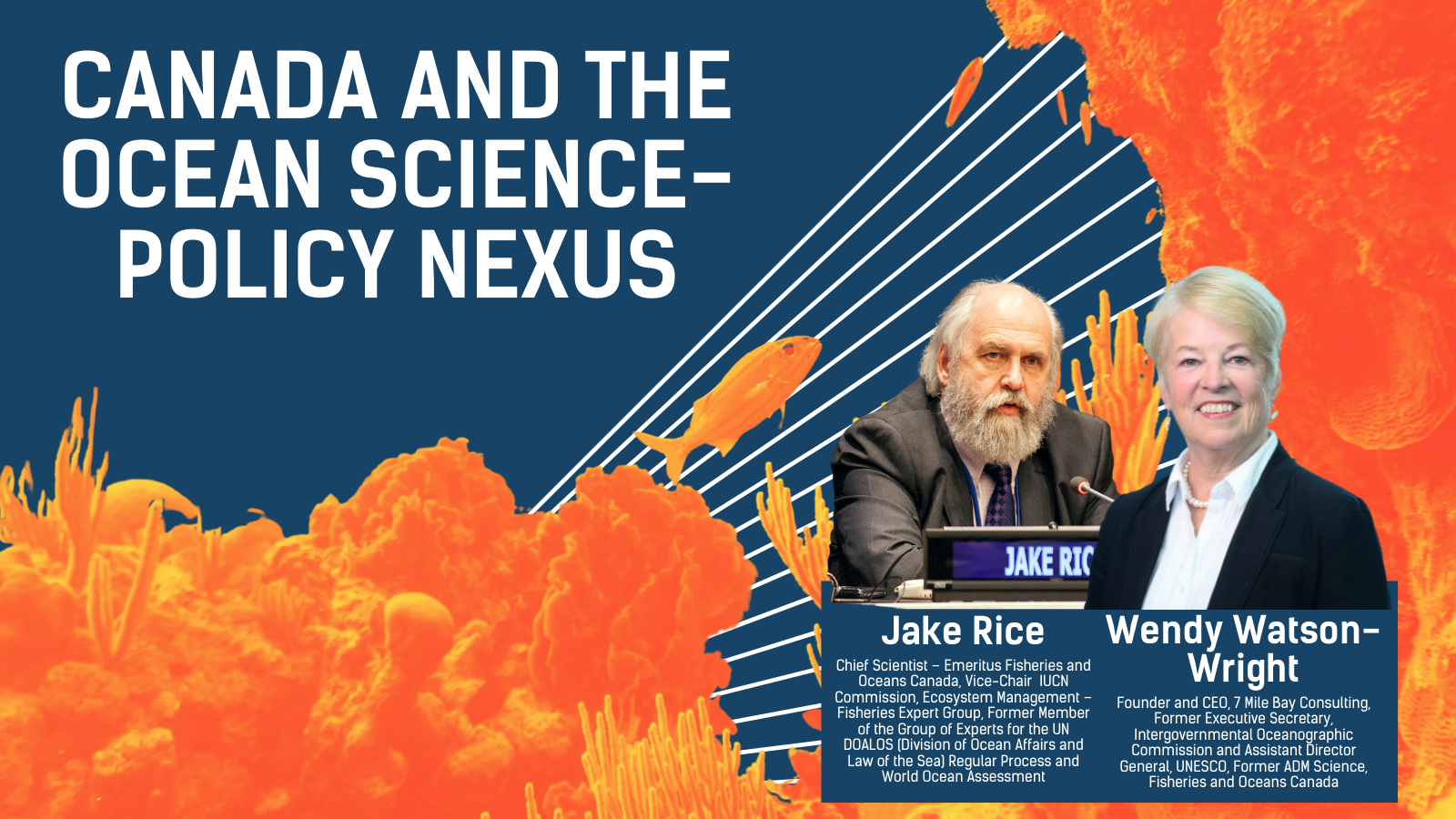

Canada and the Ocean Science-Policy Nexus

Author(s):

Jake Rice

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Chief Scientist - Emeritus

ICUN Comissions

Vice-Chair

Fisheries Expert Group

Ecosystems Management

Wendy Watson-Wright

7 Mile Bay Consulting

Founder and CEO

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

former Executive Secretary

The global ocean is our planet’s defining feature, accounting for 71% of its surface, 97% of its water and 96% of its living spaces, driving the hydrological cycle and offering more than ⅔ of Earth’s regulating, supporting, provisioning and cultural ecosystem services. Yet the ocean is facing a multitude of challenges, threatening to undermine its ability to continue to provide us with those services.

Canada has defined itself as an ocean nation since Confederation. It has by far the world’s longest coastline (>240,000 km), borders three ocean basins and is reliant on the ocean for much of our prosperity. Canada was the first country to pass an Oceans Act, and its Fisheries Act has been one of the oldest and strongest pieces of environmental legislation in the country.

On the world stage, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, years 2000 to 2015). The seventeen SDGs comprise the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SD) and are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere. Canada plays an important role, with our Prime Minister co-chairing the SDG Advocacy Group. SDG 14, Life Under Water, gives the health of the ocean explicit recognition as being essential for our future, and UN conferences devoted entirely to this SDG were held in 2017 and 2022.

Ocean science figures prominently in the 2030 SD Agenda, in that the UN General Assembly declared 2021 to 2030 the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development – “the science we need for the ocean we want”.

In terms of attempting to reconcile science and policy, the ocean realm has a unique history more than a century long. The inability of individual countries to manage ocean uses and pressures led northern European countries to establish the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in 1902. As awareness of the need to manage fisheries and sources of pollution grew, ICES developed increasingly structured processes for experts to meet, combine their knowledge, and take consistent advice back to their home countries. When the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) established Exclusive Economic Zones to 200 miles, the ICES membership expanded to the Northwest as well as Northeast Atlantic, and Canada became an essential contributor. Members (States and the EU) submit requests for scientific advice to ICES where expert Working Groups (WGs) peer review the scientific information and produce extensive scientific reports upon which experienced Science Advisory Groups base formal scientific Advisory Reports. Both the Advisory Reports and their WG reports are published, ensuring all information backing the advice is available.

Canada was among the first to develop its own formal peer review and advisory process to deal with the large responsibilities arising from our extensive jurisdictional waters. Modeled on ICES, the processes are institutionally embedded to ensure consistency and confirm that processes are adequately supported, transparent and coherent in the treatment of advisory requests. From modest beginnings primarily estimating the sizes of sustainable fishery catches, these structured processes encountered challenges, starting with keeping up with advances in data quantity and quality and the analytical methods used by the experts. These challenges grew as modern informatics technologies became available but could be met by experts comprising the WGs. However, national concerns about environmental quality, contaminants and pollution challenged these advisory processes to broaden their scope. To address these challenges, ICES and national processes attracted new suites of experts and formed additional WGs on marine pollution and habitat quality.

The 1970s and 1980s brought additional challenges. WGs documenting trends in time series found it increasingly difficult to explain both causes and consequences of the trends with simple linkages of harvest rates to stock dynamics, and pollution rates to coastal degradation. These challenges were met by additional expert WGs considering ecosystem and ocean relationships and dynamics. These WGs produced additional thematic expert reports in oceanography and marine ecology, maintaining established standards of scientific quality and peer review and allowing established Advisory Groups to incorporate ecosystem content into traditional forms of advice.

Inclusion of these more complex relationships quickly made policy makers understand that policy itself needed to take these relationships into account. This required more ambitious and inclusive policies informed by framing more complex requests to the science advisory processes. Canada’s Oceans Act of 1997 explicitly acknowledged that Canada’s ocean spaces needed to be managed as a whole, with the entire spectrum of the uses and dynamics of the ecological relationships considered central to framing advice, rather than as add-ons. This has required scientific experts to work together across disciplines of population dynamics, physical and chemical oceanography, and ecosystem processes, from basic data to final advice, while policy and management require the various sectors (fishing, aquaculture, offshore energy, etc.) to be aware of each other’s activities and plans given all operate in the same ocean. Progress has been made in science’s ability to accept broader advisory requests from policy makers and produce responses to the increasingly complex questions, but better integration requires more than an additional incremental step.

In the past decade, States have acknowledged that both climate change and the loss of biodiversity are crises that cross all sectors and can be addressed only through coherent cross-sectoral advice. Early efforts to implement provisions in the Oceans Act for marine spatial planning and marine protected areas underscored the importance of space itself as an essential and necessarily cross-sectoral component of policy and advice. This requires explicit recognition that we have ONE ocean, organized on many nested scales from global to local and shared by many users. Needs for policy and advice appear on all scales, but actions can be solutions only if they combine coherently across that one shared ocean.

Another great challenge lies in the understanding that at best we manage activities in the ocean, not the ocean itself. This comprehension breaks down the traditional boundary between advice from natural science experts and inputs “elsewhere” from social scientists. Initial efforts to include social scientists in advisory processes highlighted the importance of knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, whose input in the past was largely ignored or at most used at late stages to fill gaps in the “real” science. Some social science information can be quantitative, but much of it is narrative, as is the critical knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and must be treated as such to both respect its sources and gain its true value.

The challenges to the peer review and advisory processes have been at the core of the ocean science-policy interface for over a century. Currently, new types of WGs are being established, but their products, although interesting, have produced checkered results when efforts are made to incorporate them into traditional advisory streams. Similarly, efforts to provide truly cross-sectoral advice has made spotty and slow progress. How much more integration is needed to have an effective science-policy interface for ONE ocean with rich diversity at many nested scales, for ONE humanity with similarly rich diversity at as many scales? That is a question that needs to be answered – soon. Canada could lead the charge…if we choose to act with foresight.