Crisis management through digital social innovation

Author(s):

Anil Wasif

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed

Tahmid Hasib Khan

In the age of digital relationships, the #BacharLorai movement draws a connection between social innovation and disaster management in an online economy. As governments and billionaires run out of fuel, nudging a response from civic society could be the solution we are all looking for. The question: how do those looking to make a change, empower those in need?

If the last decade helped us turn human connections into sharing economies, this one started off asking for more. This year, a global call for collaboration using digital technology was put out to take a stand against COVID-19.

Digital Social Innovation

As people all over the world started co-creating solutions for a wide range of social needs at scales unimaginable before – we revisit the meaning of Digital Social Innovation (DSI) once again (1). While profit maximization creates the urgency for businesses to innovate (2), DSI encourages us to address social challenges in the digital economy – suggesting a new model for connecting information, data, and resources to people.

While authorities experimented with scientific measures to change health behaviour, members of the public involved others in a different way. Social nudges echoed from Italian balconies, French terraces, and Canadian patios encouraging more people to step up around the world. As these nudges started to transfer to Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, the impact of encouraging others to come together became stronger. At a time when governments and billionaires started to run out of steam, citizens stepped up to initiate change.

As the overall structural machinery stumbles at the face of the pandemic, the cracks in our socio-economic foundations have been exposed. The countries at the highest risk, in particular, being those of the Global South. With a history of responding to similar crises, the pandemic has opened up new challenges for these economies. In these regions, there is a deep correlation between population density and the virulence of infectious agents. As seen with malaria, high population density regions were more prone to multi-dimensional calamities at the onset of infectious diseases (3). Community mitigation measures during the time represented a viable solution, as grassroots approaches like community clinics, became an appropriate strategy for crisis control (4). Thus, the Global South has increasingly sought ground-up approaches to human-centric problems like the Coronavirus.

Bangladesh continues to be a nation where sustainable innovation is a constant need in its battle for survival. The persistent threat of natural disasters, the existence of inefficient crisis management systems (5) and the challenges posed by sheltering the largest refugee camp in the world (6); calls for the wide-scale mobilization of non-state actors, grassroots organizations and social innovators in one of the fastest-growing digital economies (7) today.

Owing to its adaptation of the Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care (PHC) in 1978, the healthcare infrastructure of the seventh most populous nation in the world promotes grassroots efforts towards planning, operation, and management of primary healthcare (8). Bangladesh’s adaptation of the PHC enables a shared economic model that provides appropriate tools to respond to COVID-19.

Global digital social innovation can draw inspiration from similar interventions in Bangladesh. For instance, with the success of BRAC in enhancing rural healthcare or Grameen Bank in encouraging entrepreneurship or Bkash in promoting digital banking (7). These institutions have created a space for collaboration through the use of digital technology—increasing the ability to directly support vulnerable populations in rural Bangladesh. The question remains on how we connect people to the resources mentioned above.

A social movement can be built on these success stories by encouraging individuals to become social innovators. The philosophy of a movement can focus on giving everyone equal power and authority rather than a special seat at the table; creating more meaning for a person involved. Digital social innovation drives collaboration among innovators allowing them to hack bureaucracies and take swift action beyond borders when necessary. Canadian Bangladeshis have touched on this sentiment by involving their counterparts to co-create a movement of their own.

BacharLorai (Batch-aar-Law-Rye) means ‘fighting for survival’ in Bengali.

The #BacharLorai movement connects expatriates, citizens, and grassroots organizations fighting COVID-19 through digital social innovation. It is a cross-disciplinary network to connect those who want to help, to those in need. The ecosystem enables people to start an initiative or collaborate on an existing one; individuals launch or take part in initiatives that create social impact as by-products of their economic activities. Such was the case when an artist connected with a charity through the movement to sell his art and support the economically displaced from the proceeds. Similar connections inspired more people to co-create solutions for challenges they couldn’t address alone.

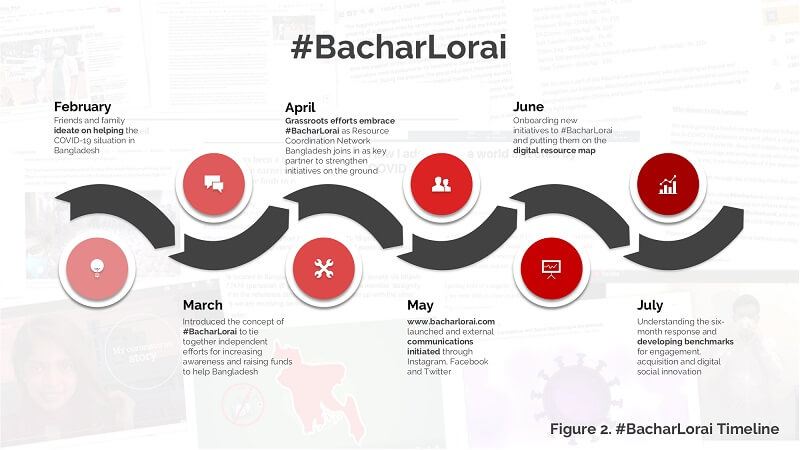

This growing network (Figure 2) has not been limited by socioeconomic class, age group, or proximity as seen previously in the Bangladeshi context. The global call for collaboration has allowed this to happen. From sons and mothers working together, to rickshaw-pullers and entrepreneurs teaching each other, #BacharLorai continues to facilitate avenues for awareness generation, aid dissemination, and supply chain creation. As the movement builds trust, bigger doors are opening, including opportunities to work with government agencies.

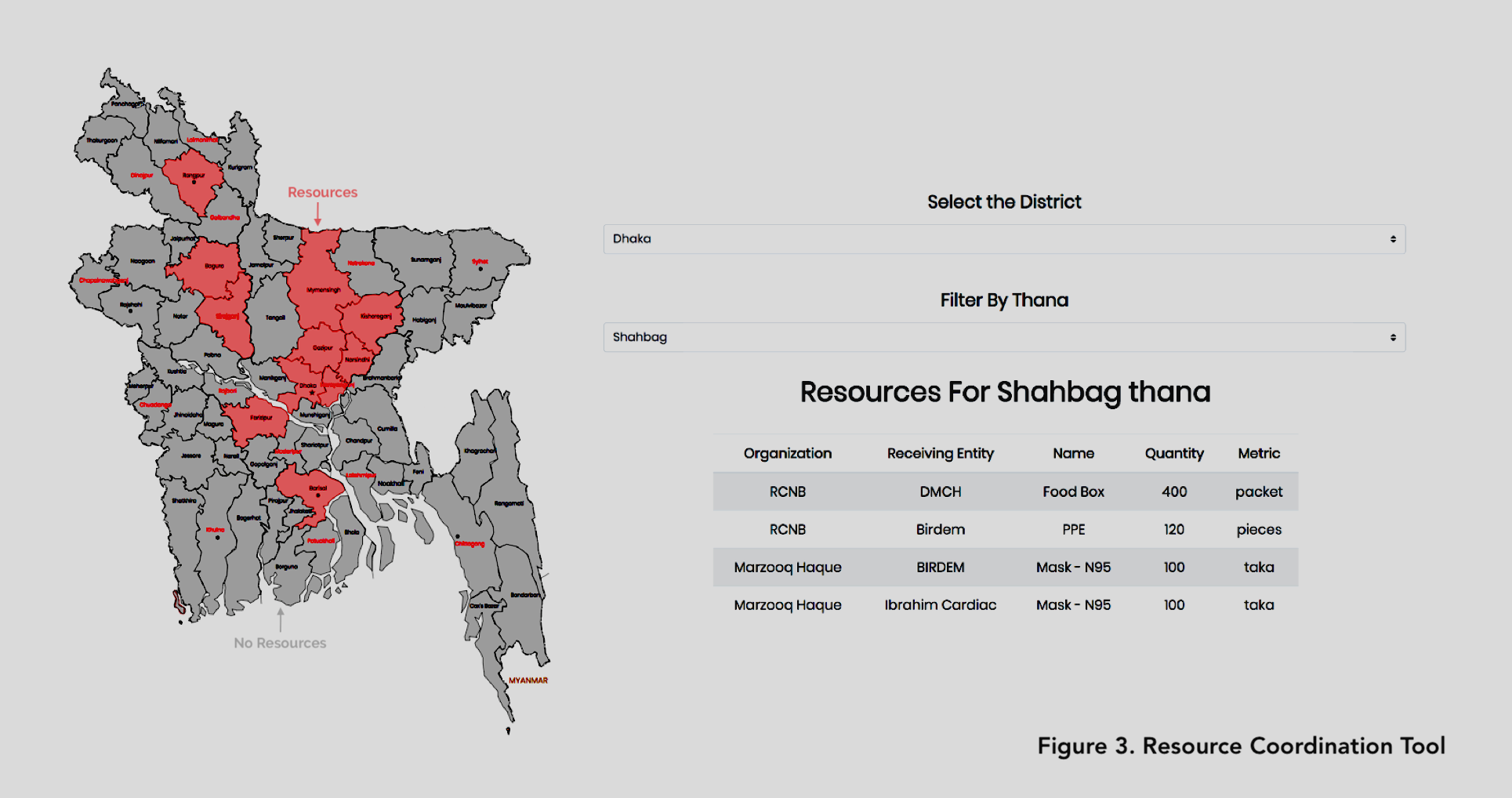

It’s difficult to assess the impact of social innovation in a digital world as there are limits to quantifying positive change (1). #BacharLorai is trying to address this with a resource coordination tool co-created by members of the movement running their initiatives. Through a digital map (Figure 3) of Bangladesh, #BacharLorai aims to show when, where, and what resources are being allocated by its contributors. By doing so people can start measuring the impact of their initiatives while simultaneously creating a one-stop resource hub for others to do the same.

Synergies between technology, social media, and relief accelerate the movement in a digital economy. Flexible involvement through voluntary efforts creates an effective ecosystem. Prioritization of local technologies like Bkash, expedites monetary resources towards affected populations. Communication on Facebook and WhatsApp fast-tracks relationships beyond borders. Intersections between the avenues mentioned above create the scope for immediate impact.

By creating a network of individuals and communities that share the same values, social movements can build capacity to inspire, inform, and integrate crisis responses in this digital age. This makes #BacharLorai a small yet integral effort in the fight against COVID-19.

Citations:

1.Bria, F. (2015), Growing a digital social ecosystem for Europe, DSI report, EU commission, December 28, 2016, from http://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/dsireport.pdf

2.Mulgan, G. (2006), The process of social innovation, in Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, Volume 1, Issue 2, The MIT Press, 2006, pp. 145-162

3.Coker, R. J., Hunter, B. M., Rudge, J. W., Liverani, M., & Hanvoravongchai, P. (2011). Emerging infectious diseases in southeast Asia: regional challenges to control. The Lancet, 377(9765), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62004-1

4.Blendon, R. J., Koonin, L. M., Benson, J. M., Cetron, M. S., Pollard, W. E., Mitchell, E. W., Weldon, K. J., & Herrmann, M. J. (2008). Public response to community mitigation measures for pandemic influenza. Emerging infectious diseases, 14(5), 778–786. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071437

5.Izumi, T & Shaw, R. (2014), A New Approach of Disaster Management in Bangladesh: Private Sector Involvement, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014

6.Hoque, S. (2020), If COVID-19 arrives in the camp, it will be devastating. https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2020/4/5e9ead964/covid-19-arrives-camp-devastating.html

7.Chen, G & Rasmussen, S. (2014), bKash Bangladesh: A Fast Start for Mobile Financial Services. CGAP Brief. https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Brief_bKash_Bangladesh_July_2014.pdf

8.UNICEF., World Health Organization., & International Conference on Primary Health Care. (1978). Declaration of Alma Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf