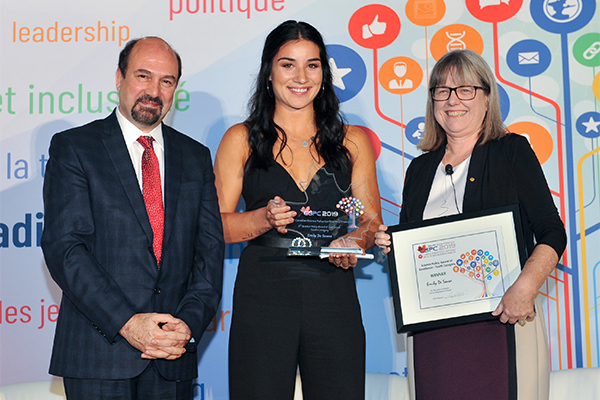

Emily De Sousa

Graduate

Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Guelph

Eliminating Seafood Fraud: A Fishy Approach to Food Policy

Connected Conference Theme:

Biography:

Emily De Sousa is a graduate student at the University of Guelph, Department of Geography, Environment, and Geomatics. Her research interests include seafood sustainability, ocean governance, and the geography of islands. She is the founder and creative director of Airplanes & Avocados, a sustainable travel brand teaching readers how to see the world and save it at the same time, as well as the founder and executive director of Youth Action on Climate Change, a community incubator dedicated to cultivating the next generation of environmental leaders. Emily is a trained PADI Divemaster and hopes to pair her love of scuba diving with her academic pursuits to continue researching the underwater world and how we interact with our oceans.

Proposal Inspiration:

“Growing up in a Portuguese household, I’ve been surrounded by seafood my entire life, peeling shrimp since before I could even walk. Growing up, this made me the weird kid with smelly lunches. As an adult, it makes me an expensive dinner date. One of the main reasons that seafood can be so expensive and inaccessible to many is due to seafood fraud: the intentional act of mislabeling for economic gain. When I learned that Canada was one of the leaders of seafood fraud, I was devastated. I immediately made the focus of my work repairing the seafood industry’s reputation and finding ways to ensure everyone has access to the most nutritious protein source on the planet.”

Need/Opportunity for Action:

Seafood is a significant source of protein for nearly 3 billion people around the world and contributes $6 billion to the Canadian economy. But a lack of coordinated policy threatens local seafood supply, specifically when it comes to seafood fraud [1,2].

Approximately 30% of seafood products around the word are mislabeled [3]. A 2018 study by OCEANA, revealed that Canada is one of the leading culprits of seafood mislabeling: 44% of seafood sold in Canada is mislabeled [3, 4].

Seafood mislabeling has dire consequences, including compromising sustainable fisheries and undermining conservation efforts by misrepresenting stock numbers [5]. Mislabeling also creates health risks for consumers, resulting in a loss of consumer trust in food supply. Potential health issues that can arise from seafood mislabeling include tetrodotoxin poisoning from puffer fish and oily diarrhea from escolar, a product which humans cannot actually digest [6, 7].

A 2016 study revealed that 55% of consumers doubt that the seafood they consume is what it says on the package [3]. This lack of consumer trust can negatively affect Canada’s seafood economy and drive consumers to avoid one of the most nutritious food sources on the planet [6].

Numerous studies have linked a variety of human health attributes directly to the consumption of sea-food. Omega-3 fatty acids derived from seafood are important for reducing inflammation and preventing the onset of diabetes. Vitamin D present in salmon is essential for healthy bone functioning. In a study conducted in the UK, children deficient in vitamin B12 experienced greater levels of anxiety and per-formed more poorly on tests than children with diets of mussels, which provide them with excess B12 [8, 9]. Additionally, mussels are one of the best natural sources of iodine, required for normal thyroid gland function in humans [9].

A recent study estimated that 5,800 diet-related deaths could be avoided every year if Canadians in-creased their consumption of fish to 150g per week, the levels recommended in Canada’s Food Guide [10]. The value of these health benefits to Canadian society is considerable; 5,800 lives saved represents a potential benefit to Canadian society of between $42 and $50 billion per year [10]. These economic impacts of seafood fraud extend to the entire industry as a whole; not only are consumers not getting what they pay for, but responsible seafood businesses are facing an unfair market competition from those not playing by the rules. This has devastating long-term consequences to responsible fishers [4]

Seafood can also be the key to addressing food security in Canada. Over 4 million Canadians are currently struggling with food insecurity [11], while a study conducted in Alaska revealed that communities with access to locally caught seafood, enjoy improved food security, especially those households at the lowest income levels [12].

Seafood is invaluable to ensuring the future of food security in Canada and providing Canadians with access to healthy and affordable food. Earlier this year, the federal government announced the first ever Food Policy for Canada with an initial investment of $134 million to help Canada build a healthier and more sustainable food system. [13].

However, until Canada addresses the fraud problem within its seafood industry, the food policy will fall short in terms of make meaningful change for all Canadians. In order to build an effective food policy, we need a reliable and sustainable seafood industry. With the longest coastline in the world, Canada should be a leader on matters pertaining to ocean sustainability, including seafood. The recommendations below seek to strengthen the mandate of the Food Policy, with the primary goal of ending seafood fraud and making seafood accessible and affordable for all Canadians.

Proposed Action:

The proposed actions are a culmination of evidence-based approaches that focus on building a more transparent seafood supply chain and supporting the vision of the Food Policy for Canada.

1. Strengthen the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations to include strict traceability regulations

Scientific literature widely advocates for transparent traceability of the entire seafood supply chain [14]. It is the most important step to ending seafood fraud. Mandatory full-chain boat-to-plate traceability would require that handlers throughout the supply chain, from fish packers to purchasers in supermarkets and restaurants, provide details about the seafood at each stage of the supply chain. [15].

Canada’s Safe Food for Canadians Regulations currently fall short of international traceability standards [16]. In order to implement full-chain boat-to-plate traceability in Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), in consultation with fishers, seafood retailers, consumers, and ocean conservation groups, must make full-chain traceability a requirement in the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations. All seafood being sold in Canada must include key information that follows fish throughout the supply chain; including who, what, where, when, and how the fish was caught, processed, and distributed.

Taking this proactive approach is the first step to building a more transparent seafood supply chain.

2. Utilize DNA barcoding as a regulatory tool

DNA barcoding is a powerful molecular tool fit for the purpose of identifying mislabeling of seafood products in Canada. The technology compares a DNA sample from a seafood product again a global data-base “the Barcode of Life Data System” which contains sequences from hundreds of thousands of species [6]. This has already proven to be a successful forensic tool in identifying mislabeled seafood in Canada [6]. The Food Policy for Canada has committed $24.4 million dollars to ending food fraud in Canada [13]. In order to effectively address food fraud, part of this funding should be directed towards sup-porting regular and randomized DNA barcoding of seafood products sold in grocery stores, retailers, and restaurants across Canada. This would allow authentication of species and ensure the integrity of the im-posed traceability regulations recommended above. It is recommended that this process be overseen by members of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the soon-to-be-developed Food Policy Council, and independent researchers who specialize in DNA barcoding.

In Canada, the only information required on seafood labels is a generic marketplace name and the country where the product was last processed [17]. This labelling method allows many species to be listed under the same common name, leading to confusion and undesired consequences. For example, in Canada more than 200 species can be listed as “snapper”. These inadequate labelling rules cheat consumers, risk their health, hurt law-abiding fishers , and can make consumers unknowing accomplices to unsustainable fishing [6, 17].

In order to finally end mislabeling, Canada’s labelling standards need to be brought up to par with other seafood labelling standards around the world [18]. All seafood products sold in Canada must be labelled with their scientific species name, information about whether the product was farmed or fished, it’s country of geographic origin, and the type of fishing gear that was used to harvest it. This method of comprehensive labelling will help more clearly identify mislabeling and has previously been suggested as a tool to help combat seafood fraud [6].