The Arctic in Changing Times: Summary of Science Policy Perspectives

Author(s):

Anirban Kundu

In the past decade, Arctic research has highlighted key drivers of climate change. This includes thawing and abrupt permafrost thaw, microbial mediated permafrost biogeochemical transformations, release of greenhouse gases, interdependencies of vegetation loss and melting ice covers and more, which leads to long-term environmental and socio-economic impacts and posing adverse effect on Northern communities. Arctic research is important to resolve the gamut of environmental, geographical, and climatic factors that govern the mechanisms above. Furthermore, in the face of the COVID-19 global pandemic, robust science policies are required to drive innovation and research in such extreme environments to i) improve mechanistic understanding of climate-change causing events, ii) enhance preparedness for the 4-million Northern communities currently inhabiting the Arctic. This is especially important for Canada, considering the country has the longest Arctic coastline globally, and is experiencing warming at 3-times higher levels than the global average. The UN Environment Programme’s Rapid Response Assessment identifies community infrastructure, field-based investigations, quantitative characterizations, contaminant mobility, capacity building and knowledge dissemination as pivots towards more effective permafrost policies.

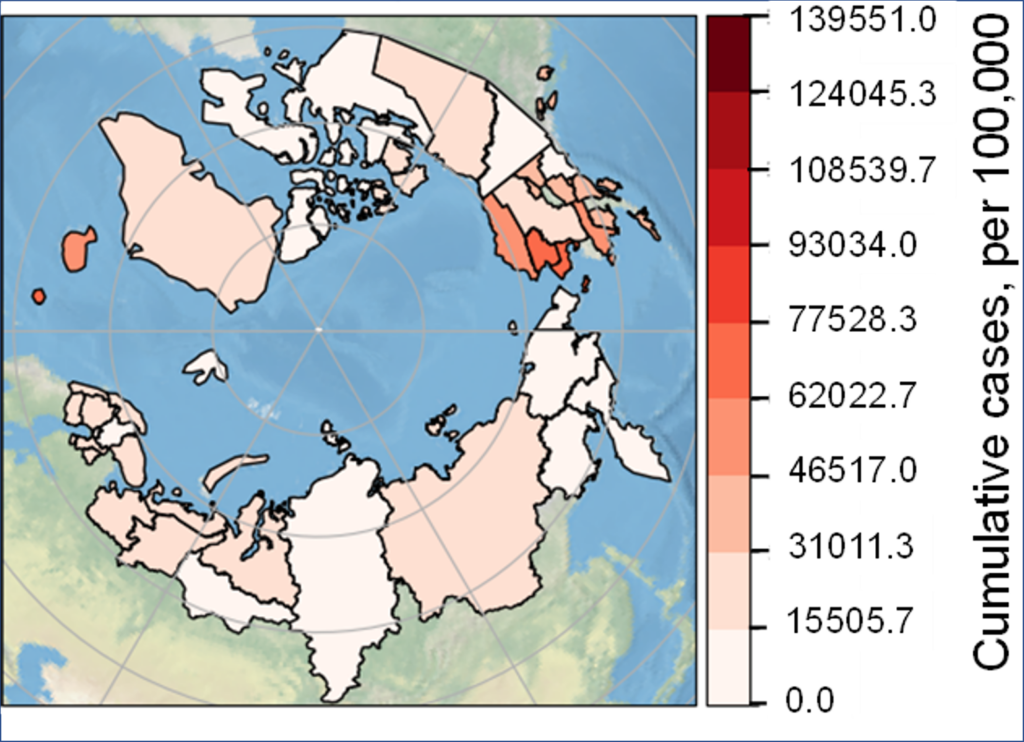

Schematic 1. Distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases in the Arctic (Source: ARCTIC Center, UNI)

As of August 2022, 2.5 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported in the Arctic (Schematic 1), with cases still rising. Poor infrastructure, remoteness, and fewer health options (versus mainland) increases the Arctic’s vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The pandemic is expected to continue, driven by variants with varying transmissibility and lethality. From the standpoint of Arctic research, the ‘new normal’ presents significant challenges to resume scientific activities on site, with particular attention to preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variants from the mainland to the Arctic’s remote communities. Robust policies are needed to address this challenge to continue permafrost research with minimum impacts on the health and environment of the communities. Some drivers include:

- Regulated travel – While travel is important for on-site research, it should be done in accordance with established mandates and guidelines set by governing organizations such as CDC (USA), The Arctic Sciences Section COVID-19 Mitigation (NSF, USA), Nunavut Research Institute (Canada), to name a few. These mandates establish preventive measures and limit the possibility of a viral outbreak in the remote research stations and observation units. Furthermore, following good practices (strict social distancing, diagnostic COVID-19 tests, pre-planning a quarantine plan, travel protocols, wearing masks etc.) is necessary.

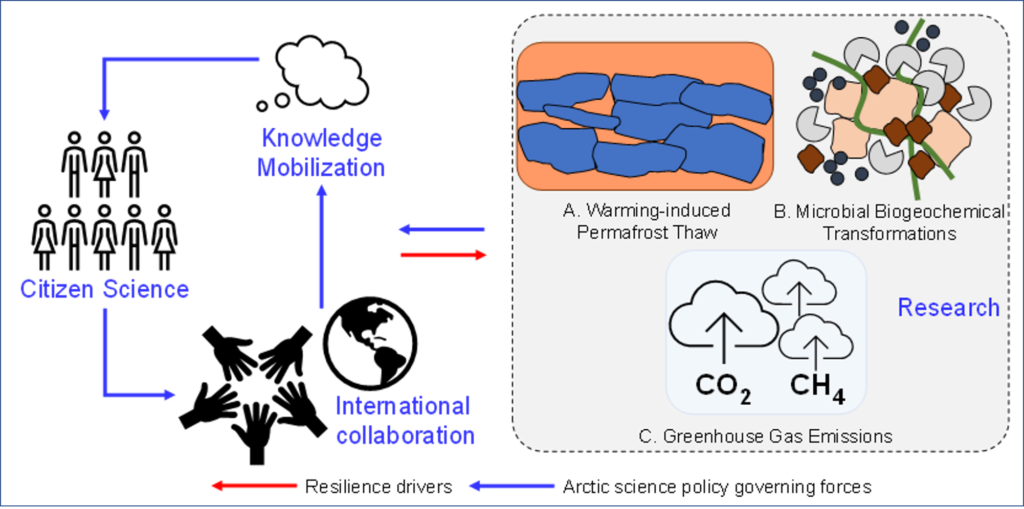

- Citizen science, inclusivity, and collaboration – The Arctic is home to over 40 Indigenous peoples, and including Indigenous perspectives is critical for continued research partnerships. This presents the scope to initiate collaborations between scientists and Indigenous communities for on-site studies and data gathering while maintaining COVID-19 protective protocols. In addition, Indigenous knowledge should be integrated into existing climate change study portfolios, enhancing understanding of ecological and natural drivers causing Arctic warming, and including Indigenous voices when shaping resiliency plans. For example, The Arctic Bears Project pooled >5000 volunteers to analyze the behavior of >2800 bear (polar, grizzly, black) subjects and assess bear habitats, interaction with the Arctic Tundra, and species diversity in the changing Arctic. Other Open Science initiatives such as Smart Arctic encourage Indigenous involvement to collect health, scientific, and education data for use by research centers.

- Pandemic preparedness and knowledge mobilization – Like the rest of the world, pandemics have had devastating impacts on the Arctic, the worst being the Spanish Flu. However presently, the propensity of pandemic spread is greater, with increased travel, exploration, research, and collaboration activities. The Arctic Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG), led by member states of Canada, US, Finland, and Norway aims to address key themes such as differential impact of public health measures and associated experiences of Northern communities, inclusion of local knowledge into public health measures, adaptation and coping strategies, future learnings for more resilient public health management. This is timely, considering a 2020 study found Indigenous populations to fare poorly than non-Indigenous populations across several health indicators (E.g., obesity, life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rate, suicide rate, tuberculosis and cancer incidence rates etc.). This indicates the need for i) effective health monitoring for Indigenous groups, ii) more robust knowledge sharing and data collection pertaining to SARS-CoV-2 variants and iii) fitting the data in epidemiology models to predict infection prevalence.

- Science diplomacy – On May 11, 2017, 8 Arctic states signed the Arctic Science Agreement as a platform of international cooperation for scientific research and development in the Arctic. In an article in Science, Dr. Paul Berkman and colleagues identify routes such as i) greater scientific mobility, ii) infrastructure, iii) integration of local and natural science knowledge, iv) research and education to identify stresses, methodologies to study these stresses, thus promote long term resilience – a big picture goal of implementing the Agreement. In the light of COVID-19 (and emerging geopolitical tensions), member states need to keep aside political differences and come together to focus on scientific research in permafrost engineering. Some pressing issues to consider for estimating the impact of physical and biological phenomena on Arctic flora and fauna, and Northern community livelihood include permafrost thaw and greenhouse gas emission, thermokarst formation, microbial transformations in the thawing permafrost, emergence of invasive species, soil physico-chemical characteristics, aerosol formation and propagation, ozone chemistry etc.

Schematic 2. Forces and Drivers for Arctic Science Policies

The Arctic is warming at 4-folds faster than the global rate. This brings risks such as abrupt permafrost thaw, loss of infrastructure, adverse impacts on flora and fauna etc. While the scientific community collectively tries to address these risks through more informed risk–assessment strategies, the global pandemic and current geopolitical tensions call for more planned and resilient strategies to continue Arctic science in a safe and sustainable manner, and in collaboration with stakeholders.

More on the Author(s)

Anirban Kundu

McGill University Canada

Ph.D. Candidate in Environmental engineering