The challenges and opportunities for the next generation in developing a science policy career during a pandemic

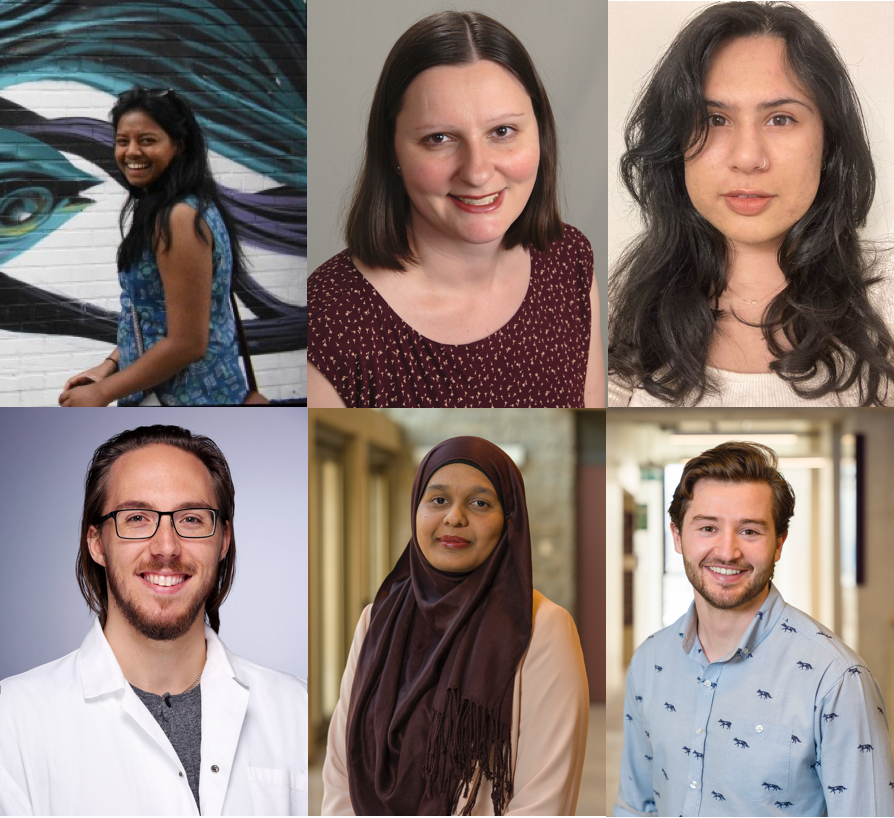

Author(s):

Saishree Badrinarayanan

Adriana Bankston

Salwa Khan

Shawn McGuirk

Farah Qaiser

Peter Serles

Volunteer. Network. Make connections. Get your face out there. Ask to chat over a coffee. These are some of the typical methods that a research trainee might use to begin building their professional network, start establishing themselves in the field, and make strides into their career. However, 2020 has been far from typical, and 2021 may present similar, and new, challenges.

With the pandemic came an entire shift in the way that we, as a society, conduct our daily life and, through that, the need to adapt every aspect of it. Research trainees aiming to launch and develop their careers are facing increasing challenges, as this is a time where face-to-face impressions and discussions are extremely valuable. How do we make the same impressions and form meaningful connections in a virtual world?

This is especially important in fields where formal training is not mandatory or even typical, such as in science policy, where connections and discussions can provide crucial stepping points towards a career. This is why, for research trainees, learning to communicate with policy professionals is essential for a career in this field, a skillset that must now be developed in the virtual space.

The pandemic has led to increased interest from research trainees in science policy, as scientists and their contributions to the policymaking process have been placed at the forefront of the crisis. Sustaining this interest beyond the pandemic and creating spaces for this training to expand will also be important for the science policy community to consider. These opportunities must be diverse and accessible. After all, if you ask six people in science policy how they began their career, you’ll likely hear six very different paths.

Opportunities in a Virtual World

Thankfully, the pandemic has created many different opportunities for research trainees to engage in science policy activities, and to gain relevant experience and valuable skills. Engaging with local Canadian groups can be a great first step to learn about the current science policy landscape and build critical skills needed to succeed in this field.

Some examples include: (1) Science & Policy Exchange (SPE, a Montreal-based non-profit organization entirely run by research trainees, which amplifies and promotes the inclusion of next generation voices in national science policy discussions); (2) Toronto Science Policy Network (TSPN, a student-run science policy group which provides a platform for individuals to learn about and engage in science policy); and (3) Evidence for Democracy (E4D, a non-partisan non-profit organization which promotes the transparent use of evidence in government decision-making). All three are hosting events and collaborating with volunteers virtually.

There are also formalized opportunities for research trainees to be involved at the intersection of science and policy, such as the Chief Science Advisor of Canada’s inaugural Youth Council, the Quebec Chief Scientist’s Comité intersectoriel étudiant, and the CIHR IHDCYH’s Youth Advisory Council.

In addition to Canada-wide engagement, the pandemic has also broken down barriers to access science policy opportunities globally, enabling research trainees to explore remote opportunities from all over the world, including conferences, such as the Canadian Science Policy Conference (CSPC) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting, and courses like the Science Policy & Advocacy Certificate Program for STEM Scientists (UC Irvine) and Graduate Certificate in Public Policy – Health and Life Science (Takshashila Institution). All of this is possible from the comfort of one’s home, and at a more affordable rate than ever before, as expenses such as travel and accommodations are no longer a barrier.

The pandemic has also broadened the horizons for science policy experts and organizations, allowing for opportunities to reach, engage and train more early-career trainees than ever before. For example, policy research and writing are critical skills for career advancement and professional development in science policy. One place to master this critical skill is the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG): a vehicle for students, post-doctoral fellows, policy fellows, and early career professionals, and young scholars of all academic backgrounds to publish on topics addressing a wide range of issues at the intersection of science, technology, innovation, public policy and governance.

In the light of the pandemic, many JSPG activities have shifted to virtual web panels and conferences, allowing early-career published authors the opportunity to engage with leading experts and participate in widely-attended conferences virtually. At the same time, this environment has allowed JSPG to continue running already existing virtual activities, such as the ongoing international science policy memo competition in collaboration with the National Science Policy Network.

The pandemic is also changing the way we work. Before, many jobs related to science policy required a move to science policy hubs, such as Canada’s capital city, Ottawa. But with remote working now expected to be the norm for the years to come, it is now possible to pursue careers in science policy virtually as the Canadian federal government and some of its science policy in-roads have adapted to virtual work. For example, many of the 2020 Mitacs Science Policy Fellows launched their fellowship virtually, and a number of fellows were selected from a special COVID-19 call for expertise. Similarly, the 2020-21 Recruitment of Policy Leaders campaign has shifted online, with particular efforts to reach scientists.

New and Exacerbated Challenges

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic has also introduced a host of new obstacles. One challenge is the perpetual isolation from one’s family and friends for extended periods of time. This has placed undue strain on the financial, physical and mental health of countless research trainees who were already disproportionately in need of greater mental health support.

The pandemic has also made it harder to network as increased screen time leads to screen fatigue. While virtual spaces have provided unique opportunities for policy enthusiasts to attend events from around the globe, the struggle to keep up with this fast paced world is an unfortunate setback. In the absence of coffee chats or casual conversations with fellow peers, the virtual science policy space can be frustrating. And for those who balance many roles or juggle between different projects, the act of multi-tasking can become particularly exhausting in the present situation, eventually leading to a faster burnout.

It is also important to note that the opportunities introduced by the pandemic are not equally accessible to all. For example, not all emerging policy professionals have access to a stable internet connection, nor the time to attend the many virtual webinars, conferences and networking sessions that are now available. These constraints are especially prominent for those with caretaking roles in the pandemic, which continue to disproportionately impact women. It is difficult to network and establish yourself as a professional, especially while balancing different responsibilities in the midst of a pandemic such as caregiving, providing for dependents, and making time for self-care, which is critical in our increasingly turbulent times.

There is also a lot of hidden knowledge that is especially difficult to access if you lack mentors, sponsors or belong to equity-seeking groups who have been traditionally underrepresented in science policy, such as Black and Indigenous communities. There are efforts to rectify the latter, such as the upcoming #BlackInSciPol week, celebrating Black members in the science policy community in January 2021, and others. Such efforts need to be supported and amplified further to ensure that under-represented professionals thrive in the science policy landscape.

But in the midst of rapid social, political, and economic change, there is space for hope. Yes, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought a number of challenges, but it has also introduced opportunities for research trainees attempting to explore the science policy landscape. For example, the pandemic has led to some governments and institutions cutting red tape, acting quickly to provide rapid and flexible research funds for COVID-19. This has resulted in new interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaborations, such as the CanCOVID network which connects experts in science, research, and policy across diverse disciplines to synthesize knowledge and inform Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There are also grassroots initiatives that have engaged research trainees in a number of ways, such as COVID-19 Resources Canada, Conquer COVID-19, and the relatively new Concordat on Mitigating COVID-19 Pandemic Effects on Research (COMPEER), which have played different roles in Canada’s pandemic response.

Build Forward Better

There is no telling how long the ripple effects of the pandemic will be felt in Canada, and across the world. It may not be enough, therefore, to consider how to build back better. Rather, we should build forward better by implementing the lessons learned from the pandemic, both good and bad.

We need to continue developing and expanding existing platforms where research trainees can gain experience, knowledge, and skills in science policy. By leveraging this new virtual infrastructure, we can create new opportunities to fill the gap and ensure that science policy is accessible to all — we can build more bridges and stronger networks, rather than restoring the silos, boundaries, and barriers that were destabilized by the pandemic. The science and policy communities should both reflect on how to build new forms of inclusive, accessible, and sustainable engagement of the next generation, who can provide fresh perspectives and creative ways to understand and solve problems in our modern world, where adaptability is critical.

Lastly, we need to continue engaging and amplifying the voices of the next generation in policy, not only for capacity building at the intersection of science and policy, but also to ensure that Canada, and the world, are better prepared for the next emergencies — many of which, such as systemic inequity and climate change, are already firmly at our doorsteps.

Resources To Explore Science Policy

- TSPN Resources page: https://tspn.ca/resources/

- NSPN Resources page: https://airtable.com/shr8J7s6QDqzX4uGz

- JSPG News page: https://www.sciencepolicyjournal.org/news

- Advice from Shawn McGuirk and Kimberly Girling (Interim Executive Director of E4D): http://blog.cdnsciencepub.com/alt-ac-careers-science-policy-advisor/