The following are the CSPC 2020 panels that cover

Trust in Science/Science Communication

Pre-Conference Day 10 – November 13th 2020

Organized by: Canadian Science Policy Centre, STEAM Sisters, Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation, Colin Stringer, Celia Du, and Anthony Morgan

Context: Public support and trust is critical for the implementation of science-based public policy, especially for high-profile, controversial issues such as climate change and public health measures in a pandemic. While evidence is used by prudent policymakers to guide decisions, ineffective communication or limited public access to such evidence erodes public trust and hinders support of science-based policy. The symposium guided attendees through contemporary challenges to communicating science during a global pandemic in a post-truth world.

Symposia Panels:

The Future of Science Communication in Society: How Has Sci Comm & Policy Responded to the COVID-19 and Other Crises to Become Resilient and a Resource in Challenging Circumstances?

Bonnie Henry – Provincial Health Officer, Province of British Columbia

Ana Sofia Barrows – Diversity and Inclusion Strategist, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Grace Jacobs – Former Executive Producer, Raw Talk Podcast

Sandhya Mylabathula – STEAM Sisters

Swapna Mylabathula – STEAM Sisters

Takeaways:

- Science communicators play an essential role as scientists may lack the expertise and training for meaningful and accessible communication for diverse audiences. This puts the onus on science communicators to share trusted information; otherwise misinformation fills the gaps.

- Science and data are not the only inputs into the decision making process. Other factors include values and judgements, policymaker priorities, financial considerations and public preference.

- The different ways people manage a crisis can inform the approach to science communication:

- CONTROL: force people to wear a mask

- AVOID/RUN AWAY: avoid dealing with it

- TAKE ADVANTAGE: blame others, stigma, scapegoating (e.g., Asian communities during COVID)

- ALTRUISM: working towards the good of others

- Online engagement is more successful when:

- Using language that tailors the message to the audience.

- The information being shared complements other information being disseminated.

- Engagement is encouraged during an event – highlight the Q&A leading up to.

- The necessary time is taken to build an online presence and attract followers.

- The message is personal.

- Engagement is inclusive, including inclusive processes (e.g., making posts, articles accessible)

- There are challenges to accessible communication, including accessible Wi-Fi, different time zones, lack of hallway conversations/communication offline, and open access to evidence.

Actions:

- Science communicators must acknowledge they do not have all the answers. Be honest with the public about the unknowns.

- Create a solution-oriented toolkit to promote effective communication in challenging times (challenges and solutions).

- There are pros and cons in switching to a virtual setting. Consider how to replace the ‘watercooler moment’ of casual conversations and settings, while supporting new and more accessible ways of communicating for different types of audiences and needs (e.g., smaller group breakout sessions that use chat, video + mic).

- Try to demystify and share the scientific process to avoid unintentionally contributing to mistrust.

Limiting the Impact of Misinformation and Disinformation; Planning, Recognition, and Response

Renee-Claude Goulet – Science Communicator, Ontario Certified Teacher

Andrea Bellemare – Reporter and Producer, CBC News

Stephan Lewandowsky – Cognitive Scientist, University of Bristol

Ahmed Al-Rawi – Assistant Professor of News, Social Media, and Public Communication, Simon Fraser University

Kimberly Girling – Interim Executive Director, Evidence for Democracy

Takeaways:

- Misinformation is false information that is spread, regardless of intent to mislead, while disinformation is deliberately spread to mislead. Disinformation often contains a kernel of truth and gets noticed because it plays on powerful emotions like fear, anger and contempt. It can be spread by “bad actors”, or even people we trust.

- There are different types of propaganda: “white” (truthful), “black” (source is concealed, aim is to deceive), and “grey” (quality of information is doubtful and its source is hidden).

- Policymakers and politicians have limited time, money and staff to invest in finding good information.

- Misinformation sticks. Many people will continue to believe the original false information even if later told it is untrue.

- People share misinformation for a variety of reasons: e.g., fear and other emotional responses; pre-existing beliefs; to warn “just in case”; mistrust of authorities.

- Algorithms on social media make it easy to share information as posts are prioritized based on engagement rather than accuracy. Organizations also use of advertisements to push false or misleading information to micro-target different populations.

Actions:

- Know how misinformation and disinformation campaigns operate, and use “inoculation” to prepare the public to face the types of mis- and disinformation they will encounter. Inoculation can provide an explicit warning of an impending threat, and refute an anticipated argument that exposes the imminent fallacy. People don’t need to know WHAT will be misleading but HOW.

- Address the process of science in communications with the public and in dialogues on evidence-based decision-making.

- What can individuals do?

- Take personal responsibility on the information you share: identify original source of information and its legitimacy; search for the story using the words “hoax, scam, or fake”; take a pause if the information triggers a strong emotional reaction.

- If you accidentally share misinformation: immediately delete it; don’t comment on a correction as it boosts the algorithm; inoculate your community by warning them of potentially false information; spread good information instead

- If you see misinformation: challenge the information and not the person (ideally via direct messaging so as not to embarrass them); focus on the majority who are not polarized and questions or have been affected by misinformation.

- Connecting strong science with the government and the public.

New Practices for Stronger Public Engagement in a Polarized, Post-Truth World: Dialogue, Curiosity and Story

Alan Nursall – President & CEO, TELUS World of Science, Edmonton

Colin Stringer – Science Communicator & Producer

Anthony Morgan – Science Communicator

Celia Du – Freelance Science Communication Practitioner

Kat Middleton – Science Advisor, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Takeaways:

- Storytelling can tackle challenges of lack of engagement on polarizing topics. Evidence shows that people internalize stories more often than facts.

- “Narrative transportation” and personal stories are effective ways to communicate science. Engagement is motivated by strong characters who are motivated, interesting, and how a desire to overcome conflict.

- Stories are more effective when they’re told by people with skill and integrity.

- Evidence shows that curiosity reduces polarization which can be encouraged through the inventiveness and thinking that comes from play. In contrast, anger and outrage leads to a desire to find certainty which can contribute to polarization.

- Different views are also legitimate. Dialogue can end when people try to convince others, when there is a power dynamic and when there is an introvert and extrovert.

Actions:

- Infographics are a good way to disseminate information: find people who can help you do this work (graphic designers).

- Prioritize listening and information sharing and find ways to equalize voices (e.g., in non-live audio capacities).

- Foster a creative and fun environment to encourage curiosity to help reduce polarization.

- For effective dialogue, drop titles and participate in active listening.

Conference Day 4– November 20th 2020

Organized by: ISED

Panelists:

Timothy Caulfield – Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy, University of Alberta

Michelle Driedger – Professor, University of Manitoba

Anton Holland – President and CEO, NIVA Inc.

Gabrielle Lim – Researcher, Harvard University

Eric Meslin – President and CEO, Council of Canadian Academies (CCA)

Farah Qaiser – Co-Founder, Toronto Science Policy Network

Context: The rapidly changing media environment of the 21st century continues to impact many facets of society. The degree to which misinformation permeates this new media landscape threatens public health policy implementation directly, and the democratic process indirectly. Multiple platforms, unchecked claims, and viral sharing of opinions also threaten the ability of Canadians to equip themselves with the knowledge they need to adapt, be resilient, and make informed decisions about their health and recommendations from elected and appointed leaders. The panel explored how Canada is addressing the challenge of science misinformation broadly and discussed the impact of both science and health misinformation in the post-pandemic context.

Takeaways:

- There is a documented increase of scientific misinformation contributing to what the World Health Organization has termed an “infodemic” that is causing real, substantial and measurable harm to people (e.g., a 2020 study estimated that 800 deaths have been linked to the inaccurate claim that concentrated alcohol is a cure for COVID-19. This situation is likely exacerbated by social media platform algorithms, which have been criticized for creating “echo chambers”, where we only see information that confirms existing beliefs, blocks other perspectives, or recommends sensational but dubious content).

- Misinformation and its related cousin, disinformation (intentionally misleading information), are more easily spread where there is incomplete or evolving information for making policy decisions.

- While trust in science has been stable over time, trust in scientists and scientific institutions has decreased.

- Evidence suggests that concerns of “backfire effects” are overstated (i.e., the idea that debunking helps to amplify misinformation and entrenches views).

Actions:

- Debunking strategies are effective and need to be applied more widely and strategically. This includes reporting misinformation to the appropriate authorities, using facts from trusted sources, and being authentic, empathetic and humble when countering misinformation.

- Improved science literacy is crucial to containing the spread of health misinformation and mitigating against its harms. Start with good science and use creative approaches such as storytelling and art. Remember that the general public, NOT hard core deniers, are the key audience.

- Engage with communities where they are and consider inclusion in all aspects of communication, such as ensuring that there is public health guidance available in multiple languages, in addition to English and French.

- Training scientists in science communication is essential for them to not only share their research broadly, but also to effectively counter misinformation. For this to be possible, both academic institutions and federal funding agencies need to allocate funding to support existing training initiatives and expand training opportunities further.

- Using proven risk communication strategies early on can mitigate the potential for misinformation problems downstream.

- Social media platforms can take more action to prevent the spread of health misinformation and disinformation.

- Preprints are a double-edged sword. While they are important for supporting open science, pre-prints have contributed to misinformation during COVID-19 and have created serious concerns. The public should treat pre-prints with caution, and the mainstream media should report on them cautiously.

Conference Day 1 – November 16th 2020

Organized by: Institute on Governance

Panelists:

Jeff Kinder – Executive Director, Science and Innovation Institute on Governance

Rob Annan – President & CEO, Genome Canada

Marga Gual Soler – Science Diplomat Expert, Young Global Leader, World Economic Forum

Rhonda Moore – Practice Lead in Science and Innovation, Institute on Governance, Ottawa

Shobita Parthasarathy – Director, Science, Technology, and Public Policy Program, University of Michigan

Context: The postwar “social contract” between science and society is now 75 years old and showing signs of strain. Skepticism and distrust in science are on the rise; climate change denial and anti-vaccination sentiments are signs of a public that is unsure about the value of science in their lives. Meanwhile, the traditional emphasis on fundamental science within disciplines results in missed opportunities for more inclusive and interdisciplinary, challenge-oriented approaches to public science. This international panel discussed the elements of a new social contract, and how to rebuild the relationship between science and society.

Takeaways:

- Social contracts need to focus on ordinary citizens, communities and society’s priorities. The lack of a healthy balance between science, polity and society can lead to growing distrust in science. Improved civic education and awareness of both science and scientific organizations can increase public trust which can strengthen the scientific enterprise.

- Science and technology policies while seeminly inclusive, are often not immune to inherent structural biases (i.e., community-based differences to the pandemic response). This leads to many communities and marginalized groups feeling disenfranchised and hence disengaged from the scientific process.

- Much of the distrust in science also stems from the lack of understanding of the scientific community regarding the barriers. Open science and citizen science tends to cater to those who are proactively engaged.

- Scientists need to act without political bias. Having a political leader who is able to make evidence-based decisions without political bias is equally crucial for the social contract to remain relevant.

- Science diplomacy and international collaboration with a common global agenda are necessary, as they bring together experts beyond boundaries to serve global interests.

Actions:

- Science and technology policies need to be restructured:

- with a deeper understanding of the structural biases that exists within the policies,

- to include and better serve society, especially marginalised communities, and

- to incorporate local and indigenous expertise by reconciling with the native communities.

- Train scientists to understand the policy implications of their research. This also requires training government and other sectors to understand that scientists should be everywhere in society not just research labs.

- Go beyond the “information deficit” between science and society. Scientists need to focus less on using data as their explanation and consider the drivers that exist beyond the ability of someone to understand science. Focus on people’s emotional drivers/fears that lie below the data.

- Scientists need to look at the structure of institutional incentives. If we want to ensure scientists are providing public good, then we need to make sure institutional incentives are aligned to drive this.

- A mission-driven approach requires defining exactly what the mission is. There is a need to consider diverse viewpoints, including marginalized community, to ensure the outcomes are inclusive and equitable. The inclusion and growth of fundamental research is also crucial.

Conference Day 2 – November 17th 2020

Organized by: Institute for Science, Society and Policy

Panelists:

Monica Gattinger – Director, Institute for Science, Society and Policy and Professor, University of Ottawa

Rhonda Moore – Practice Lead in Science and Innovation, Institute on Governance, Ottawa

Rachel Bitecofer – Host, The Election Whisperer

Niilo Edwards – Executive Director, First Nations Major Project Coalition

Preston Manning – Manning Foundation for Democratic Education

Context: Polarization is on the rise globally, and has the potential to challenge the societal mobilization necessary to address the grand challenges of our time—from climate change and energy security to global health. But how polarized are we, and on what issues? How can decision-makers, the scientific community, and science communicators chart a path forward for policy and communications when citizens and leaders disagree strongly and irreconcilably? What tactics, approaches and strategies work? This panel brought together experts and political, Indigenous and non-profit leaders from Canada and the US to tackle these important questions, drawing on emerging research and fresh insights.

Takeaways:

- If the public is “fragmented” on an issue, opinions are spread more evenly across the spectrum, with roughly even numbers in agreement and disagreement. If the public is “polarized” on an issue, opinions cluster at the extreme ends of the spectrum. People do not just disagree, they disagree strongly. Understanding where the public is fragmented vs. polarized is important, as it provides some sense of where people may be more open to compromise.

- Polarization is not healthy for democratic processes. It creates division, makes governance difficult, and contributes to a decline in public perception of political processes. It is also not healthy for science – it can lead to misuse of science and science denial.

- Moving fast does not necessarily mean moving effectively. Many of our institutions do not afford us the time that is needed to establish productive partnerships, build trust and make informed decisions.

- Lack of trust (i.e., in science, institutions, etc.) can lead to polarization. Indigenous communities may have inherent lack of trust due to their colonial history.

- Indigenous communities are not always given all the necessary information on major projects, or enough time to review the information under tight regulatory timelines. This can lead to polarization among community members and challenges in decision-making.

Actions:

- Finding commonalities is important for bridging the gap on polarizing topics. Shared narratives and empathy are tools to help find commonalities (see Driving Dialogue and Debate, a recent report from Institute on Governance).

- Scientists can often be fixated on being right, rather than on being open. Humility, patience and listening are important tools for open debate.

- Indigenous-led organizations and those that reflect the values and priorities of Indigenous communities can be successful in building trust with communities.

- Rules-based processes and transparency in policy and decision-making are needed to build trust.

- Scientists can contribute to policy without feeding into polarization by focusing on a cross-partisan approach and not just on the party in power, establishing connections with the political community (outside of seeking funding), and putting scientific messages into a politically communicative form. Scientists should seek to be the principal public spokespersons for their science and its relevance to public policy, rather than surrendering this role to politicians or media commentators.

Conference Day 1 – November 16th 2020

Organized by: Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues United Nations NGO; McGill University

Panelists:

Mehrgol Tiv – Ph.D. Candidate, McGill University

Angel W Colón Rivera – Senior Policy Advisor to US Senator Robert Menendez, United States Senate

Maya Godbole – PhD Candidate , City University of New York (CUNY)

David Livert – Associate Professor of Psychology, Pennsylvania State University

Laurel Peterson – Associate Professor of Psychology, Bryn Mar College

Priyadharshany Sandanapitchai – Research Associate, Rutgers University

Peter R Walker – UN/NGO Representative, Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI)

Context: This panel of academics, UN representatives, and a US policy advisor share a background in psychological science. Together, they provided insight on five psychological domains (community resilience, vulnerable groups, interpersonal relationships, mental health, and human cognition) that are common both to the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change and how they can be leveraged to develop effective social policy.

Takeaways:

- Social and behavioral sciences, such as psychology, provide critical insight into human behavior that can be leveraged to address global crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic and global climate change, in a holistic, human rights-centred manner.

- Community groups and interpersonal relationships are essential to supporting local resilience during crises.

- Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change disproportionately affect certain groups, exacerbating existing social inequities.

- COVID-19 and climate change crises share similar impacts on mental health.

- Challenges to cognition for these crises include psychological distance (cognitively distant events more incomprehensible) and present bias (current events considered more important than future ones).

- There are huge ideological gaps (e.g., regarding climate change) in the U.S. and policymakers need to bridge these gaps. To do so requires psychological tools, but also political will.

Actions:

- Acknowledge and increase awareness of group disparities (which requires collecting data). Increase representation and participation of members of vulnerable populations in decision-making.

- We risk ignoring mental health during crises. It is important to acknowledge the importance of mental wellbeing, destigmatize mental health care and provide tailored and evidence-based support during crises.

- Some tools that encourage behaviours include the use of personal narratives (e.g., use stories of socially similar others) and enhancing positive prototypes (i.e., images of a typical person who engages in the behaviour).

- Greater cross-talk between policymakers and psychological scientists will ensure bottom-up and top-down actions to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 and climate change.

Conference Day 2 – November 18th 2020

Organized by: Ryerson University/ Science Everywhere

Panelists:

Anthony Morgan – Science Communicator

Conference Day 4 – November 20th 2020

Organized by: OpenTheBox (Consultancy) Ltd

Panelists:

Sylvaiane Duval – Director, OpenTheBox Ltd.

Conference Day 4 – November 20th 2020

Organized by: Center for Research on North America, UNAM

Panelists:

Camelia Tigau – Researcher, Skilled Migration, Center for Research on North America at UNAM

Conference Day 1 – November 16th 2020

Organized by: Canadian Association of Science Centres

Panelists:

Sarah Gallagher – Associate Professor, Physics and Astronomy, Western University

Dina AlKhooly – Director of Research and Evaluation, Visions of Science Network for Learning Inc (VoSNL)

Cari McIlduff – Research Fellow, Indigenous Community-Based Health Research Lab, Morning Star Lodge

Tracy Calogneros – CEO, The Exploration Science Centre & Museum

Cécile Rousseau – MD, Director Transcultural Child Psychiatry Clinic, Montreal Children’s Hospital

Context: Canadians will be living with the potential of COVID-19 infection for the next few years and must make everyday choices about how to keep themselves and their families safe. A communications campaign is required to build overarching (1) knowledge, (2) habits, and (3) public norms to reduce the potential impact of subsequent waves and help mount a successful societal response with voluntary adoption as required. Such a campaign begins with research into ways to effectively and repeatedly engage diverse populations that influence the likelihood that they would, for example, adhere to a stay-at-home directive, maintain physical distance, and wear a mask. Effective communications require developing relevant language to be used by trusted messengers that belong to diverse communities. Clear policies are also needed that address partnership and co-development models with community organizations to help enable these campaigns.

Takeaways:

- Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, people have turned to the science centre network and to the individual science centres and museums in their communities for information on staying safe.

- An effective communications campaign builds knowledge, habits, and public norms to reduce the potential impact of subsequent waves, and helps to mount a successful societal response.

- Effective communications require developing relevant language to be used by trusted messengers that belong to diverse communities.

- Effective science communication, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, must handle the delicate balance of people demonstrating healthy critical thinking but not rejecting information that is demonstrated to be relevant and scientifically based.

Actions:

- There needs to be a greater focus on building knowledge and understanding science to empower communities to make decisions that are evidence-informed and that make sense for their environmental context.

- More research into ways to effectively and repeatedly engage diverse populations is needed.

- We need clear policies that address partnership and co-development models with community organizations (e.g., community centres, science centres) to help enable these campaigns.

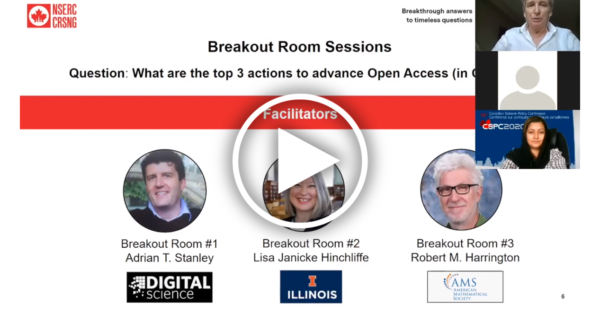

Pre-Conference Day 6 – November 9th 2020

Organized by: NSERC

Panelists:

Kevin Fitzgibbons – Acting Vice President, Communications, Corporate and International Affairs, NSERC

Vincent Larivière – Professor of Information Science, University of Montreal

Mylène Deschênes – Director of ethics and legal affairs , Les Fonds de recherche du Québec

Suzanne Kettley – Executive Director, Canadian Science Publishing (CSP)

Susan Haigh – Executive Director, Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL)

Clare Appavoo – Executive Director, Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN)

Lorna Williams – Associate Professor Emeritus, Indigenous Education

Context: COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of Open Access (OA) in an unprecedented way. Publishers have taken down paywalls, new platforms and infrastructure have emerged to support the rapid and open sharing of research, and funders and government science advisors have called for immediate OA to research results (including publications). However, the need to rapidly disseminate research results during the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed fragilities, such as the often slow publishing process, in our research ecosystem. Session participants will engage in group discussions with Canadian and international experts, on how the pandemic is impacting scholarly publishing and how to sustain a more open system to explore the question: “Where do we go from here?”

Takeaways:

- The growing use of “preprints” (draft research papers that are shared publicly before being peer reviewed) has proven vital for the rapid exchange of information and for informing public policy.

- The public and policymakers need to understand that preprints are not the same as peer-reviewed.

- Research funders provide some money for OA but it is not necessarily for gold-standard OA or article processing charges.

Actions:

- Enforcement isn’t enough. Scientists also need incentives to share their research findings (including background data) through OA. Funders can do this by following the recommendations of the Declaration on Research Assessment and academic institutions can include OA compliance when considering tenure.

- Scientists can play a more visible role in helping politicians and the public understand scientific information they see online, or in OA publications.

- OA science needs to be accessible, meaning that anyone can access it and also understand it. Avoid jargon and incorporate plain language summaries.

- Funders should consider the various publishing infrastructures, including repositories, as part of the overall research infrastructure and fund it accordingly (e.g., align with Plan S)

- Targeted money for OA from funders should also cover gold-standard OA publications and article processing charges.

- An ecosystem approach is needed that takes a collaborative approach to advancing OA. Considering convening academic libraries, publishers, funders, chief science advisors and other stakeholders, perhaps through a Canadian OA taskforce, to discuss a range of sustainable business models, as one size will not fit all.

- Ensure someone is in charge of promoting OA on campus, or create an institutional compliance office to enforce mandates from funders.

Resources:

- Roadmap for Open Science, Office of the Chief Science Advisor of Canada

- Tri-Agency Open Access Policy on Publications