COVID-19 highlights the strengths of the world’s health research system – and some much-needed improvements

Author(s):

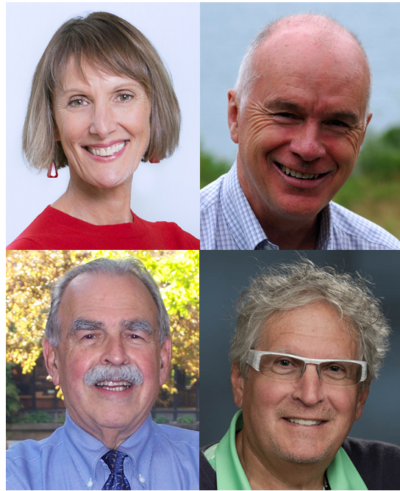

Bev Holmes

Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research

CEO

Alex MacKenzie

University of Ottawa

MD and Professor, Pediatrics

Bruce McManus

University of British Columbia

MD and Professor Emeritus

Aubie Angel

Massey College

MD, Professor Emeritus

Friends of CIHR

President

While the world has benefitted from a golden age of health science – including addressing a global pandemic with unprecedented speed – the research enterprise needs to address some major challenges of its own if it’s to help solve the wicked problems ahead of us. That was the assessment of some of Canada and the UK’s top research leaders in a sobering online discussion as part of the 2020 Henry G. Friesen International Prize in Health Research proceedings.

Awarded to Sir Mark Walport, former UK Chief Scientific Advisor and founding head of UK Research and Innovation, the Friends of Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FCIHR) prize motivated Canada’s Chief Science Advisor, researchers, and university and funding agency presidents on two continents to debate familiar themes with a renewed urgency:

Culture of the research enterprise

The pandemic has emphasized the importance of research across disciplines and beyond medicine and health, including the social sciences, arts and engineering, and investigation of social determinants of health. Researchers are willing to collaborate across disciplines, but the existing system rewards them for competing with each other for funds and recognition. There’s a corresponding tension between research investments in areas directly related to health and those that affect health in less obvious but socially significant ways, for example housing, income, employment and education. Finally, systemic racism and sexism persist in the research enterprise itself. More diversity in research leadership would help bring about much-needed culture changes.

Top down and bottom up

History demonstrates the critical importance of discovery or “curiosity” research, but science must tackle the questions of policy makers, and of society more broadly. With effort, it is possible to balance a free market of ideas and the sometimes lengthy time needed for their realization, with a societal responsibility to respond to urgent issues of the day. With the world confronting crises in addition to the pandemic – including health and educational inequalities, population hyper-densities, economic frailties, systemic racism, persistent poverty and global warming – the results of science in decision-making have never been more important. Standing structures are needed to support discussion and action among academia, government, industry and civil society, to help achieve the balance between bottom up ideas and top down societal questions.

The next generation

Young scientists need to be engaged and supported, and their creativity, energy and insights allowed free rein to make important breakthroughs. There is strong evidence that the pandemic, superimposed on a system already focused on individual competition, is compromising the careers of young investigators – and worryingly, their perception of the viability of science as a profession. Coordinated action by governments, funders and research leaders is needed. Solutions must include attention to the recruitment of underrepresented segments of society into the research enterprise. New definitions of success beyond high impact publications will encourage bigger, better and bolder inquiry.

Science in society, with society, for society

Never has the need for clear scientific communication been greater, given the profusion of counter-productive and incorrect information circulating in the public sphere during the pandemic. This communication is not only one way, from scientists to the public, but between scientists, and among scientists and citizens. We suggest 2021 should be a year for significant efforts related to scientific engagement.

Strengthening science as a public good

The foundations of the global research system are being challenged, but the valuable lesson in COVID-19 is that science can be better supported, coordinated and informed for greater societal benefits. Canada and the UK are well positioned to partner on realizing these benefits. Our universities, research institutes and funders can both look within to resolve some acknowledged – and now heightened – research system issues, and reach out to governments, industry and civil society to co-develop sustainable and effective solutions to the world’s most pressing health problems.

The Friesen Prize presentation and panel discussion can be viewed here.