Nominate Her: Women’s Participation in Electoral Politics

Author(s):

Anil Wasif

Ontario Government

Senior Consultant

BacharLorai

Co-Founder

Public Policy Association of Graduate Students (PPAGS)

President

Maisha Kabir

The Diversity Org

Vice President

BacharLorai

Editor-in-Chief

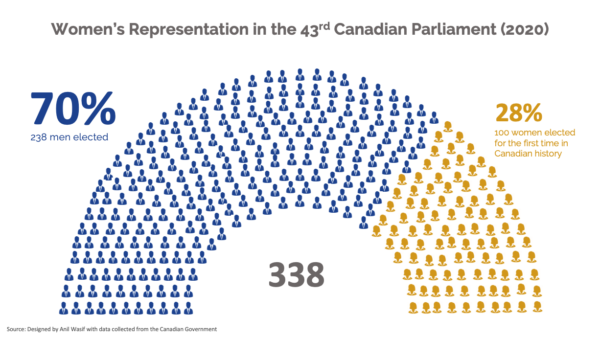

In 1921 Agnes Macphail clinched one of 235 seats to become elected as the first Canadian woman in the House of Commons. Almost 100 years later, women secured their first century of elected offices in the 43rd Canadian Parliament. While the number 100 appears celebratory, a closer look reveals a modest 28% increase in women’s representation since Macphail’s election. As the pandemic continues to widen gender gaps [1] across the Great White North, now more than ever, we must hyper-focus on women’s participation in national electoral politics, as upholding a right fought for by Macphail and others alike, would be the Canadian thing to do.

Community leadership is considered a likely pathway to Parliament Hill. Despite being informal flag bearers in their communities, women are less likely to enter electoral politics — often being ones who change rather than win elections. When they do run, often they are uphill battlers [2] against former premiers, Olympic medalists and multiple-term winners. The overwhelming statistic: less than 15% of female nominees won their campaigns [3] since 1921.

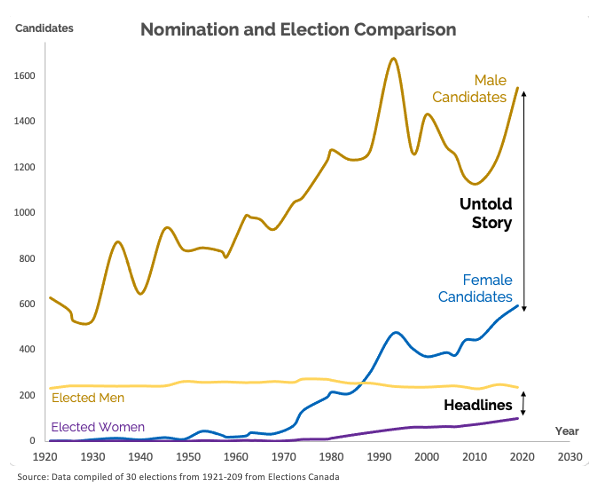

“More Women Elected Than Ever Before” is the familiar headline we see post-elections but observing election participation over the century reveals an untold story. As we celebrate steps towards gender parity in elected offices, a closer look at the difference in participation between men and women highlights that the gap in electoral participation has actually deteriorated since 1921. Today, perhaps the biggest roadblock to Parliament Hill lies in nomination.

The punctuation created by the pandemic can shift us away from the incremental style of policy making to one that calls for innovation and speed. Therefore, it is important to identify the factors preventing women’s participation in electoral politics in order to work towards a gender balanced parliament 100 years in the making. The policy window has swung open and it begs a simple question: Why aren’t more women running for office?

Lack of confidence is the preliminary basis for why more women don’t pursue electoral politics — a factor that forms quite early on in one’s childhood. By not prioritizing and practicing confidence building and assertiveness early on [4] , women downplay their skills later in life. This causes women to doubt their political potential, reducing interest in running for office.

In college, women encounter and are exposed to rape, sexual violence and harassment, which influences their career choice and further contributes to women doubting their ability to run for office. According to a Brookings study, when in high school, both genders expressed similar interest or the lack thereof for running for office. However, once in college, men were two times [5] more likely than women to assert a definite interest in running for office. Gender-based violence and harassment that women face quite early on thus becomes a major factor as to why more women don’t pursue electoral politics. This is an even bigger issue for women who identify as LGBTQIA or are of color as the intersectionality further contributes to gender-based violence and harassment.

Women are six times [6] less likely than men to be appointed as candidates. This underrepresentation is another reason why more women don’t have the impetus for pursuing elected office and are more likely to sign up as volunteers instead.

Political establishments, i.e. “gatekeepers” nominate candidates that have easy access to money. [7] Women, on average, earn less than men. Men not only raise more money than women, but they also donate more [8] to male candidates. Financing their nomination and election campaign thus becomes a major barrier to electoral politics for women, and an even greater deterrent for women of color. [9]

The media, far too often, contributes to negative stereotypes when covering women in politics. Women politicians are often asked about their appearance and personal life, i.e. “negative viability coverage” [10] whereas men are questioned about their political agenda. Women also typically receive less coverage [9] by the media in comparison to their male counterparts. Such gendered media coverage dissuades citizens from voting for women, lowers women’s confidence in their political ability and as a result, discourages them [11] from running for office altogether.

Gender stereotyping and discrimination are consequential and recurring factors contributing to women’s low electoral participation. Explicit sexism is based on gender stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination. One in five [6] Canadians hold explicit sexist views; these individuals may choose to not nominate or vote for female candidates. Women internalize this kind of overt sexism present in politics, which contributes to their lack of confidence, and ultimately a declined interest in running for office.

While Canada champions itself as a beacon of diversity, we are behind 60 countries [12] with regards to women’s participation in national electoral politics — nearly a century after granting the right for women to run in elections. Many refer to legal quotas when it comes to increasing women’s participation, but a check-box answer to the problem is hardly appreciated by generation Y. Women’s groups in North America have also rescinded their support on legal quotas in favor of training and education [13] for holding political office. However, when formulating training programs that foster diversity, policymakers need to be mindful of the assumptions they are making – for more often than not, their one-sized programs strive to fit all.

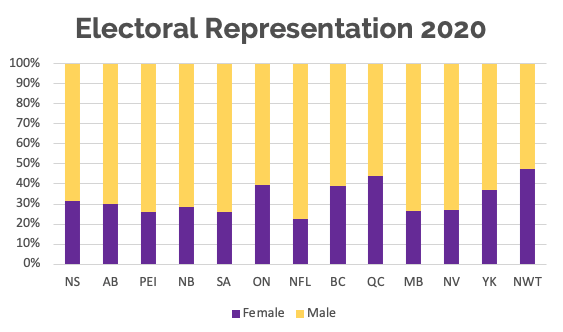

In regard to increasing education and understanding of a woman’s political career, perhaps a human rights-based approach is the way to go. While gender parity in the House of Commons is at an all-time high, it falls short of the UN’s recommended 30% critical-mass threshold [14] for female decision makers in government.

The federal focus shouldn’t distract us from realizing provincial disproportionality in women’s representation. However, the gap seems to be closing within each province as more women participate in the provincial level. Perhaps it’s the closer proximity to civil society institutions that’s increasing the prevalence of female leaders at lower levels of government.

To emulate representation at a federal level, we must go back to the basics: empowering Her to run for office.

References

- Mangione, K. (2020, July 07). When it comes to going back to work, COVID-19 is impacting Canadian mothers more than fathers: Study. Retrieved from https://bc.ctvnews.ca/when-it-comes-to-going-back-to-work-covid-19-is-impacting-canadian-mothers-more-than-fathers-study-1.5014244

- Kirkey, S. (2019, November 07). From Lisa Raitt to Renata Ford, these are the five high-profile women who lost Monday. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/from-lisa-raitt-to-renata-ford-these-are-the-five-high-profile-women-who-lost-monday

- Heard, A. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.sfu.ca/~aheard/elections/women-elected.html

- Elect Her: A Roadmap for Improving the Representation of … (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.legco.gov.hk/general/english/library/stay_informed_parliamentary_news/representation_of_women.pdf

- Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2016, July 28). Not a ‘Year of the Woman’…and 2036 Doesn’t Look So Good Either. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/not-a-year-of-the-woman-and-2036-doesnt-look-so-good-either/

- Evidence – FEWO (42-1) – No. 108 – House of Commons of Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/FEWO/meeting-108/evidence

- Warner, J. (n.d.). Opening the Gates. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2017/05/19/427206/opening-the-gates/

- Evidence – FEWO (42-1) – No. 109 – House of Commons of Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/FEWO/meeting-109/evidence

- Publications – CRIAW-ICREF. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.criaw-icref.ca/en/page/publications-action-on-barriers

- Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender Differences in Political Media Coverage: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114-143. doi:10.1093/joc/jqz046

- Wasburn, P. C., & Wasburn, M. H. (2011). Media coverage of women in politics: The curious case of Sarah Palin. Media, Culture & Society, 33(7), 1027-1041. doi:10.1177/0163443711415744

- Women in National Parliament – Inter-Parliamentary Union. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm

- Feminist Interventions in Political Representation in the … (n.d.). Retrieved from https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10502

- Equal Participation of Women and Men in Decision-Making … (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/eql-men/FinalReport.pdf