Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Remarks and One-on-One

Keynote session with Minister of Science, Honourable Kirsty Duncan. A 3-point plan for re-energizing Canadian science

Takeaways and recommendations:

A 3-point plan for re-energizing Canadian science

#1: Strengthen science

#2: Strengthen evidence-based decision making

#3: Strengthen the culture of curiosity in Canada

Science minister Kirsty Duncan used her keynote at this year’s Canadian Science Policy Conference to outline her government’s three-point plan for re-energizing Canadian science.

“Right now, Canada is seen around the world as a progressive country empowering its scientists to make breakthroughs that could change the way we understand ourselves and the world around us,” she told delegates. “I believe we have an opportunity to seize the moment and fulfill a vision that promotes Canada as an internationally recognized champion of science and scientists.”

The three priorities were informed, in large part, by the recommendations made in Canada’s Fundamental Science Review. The independent review panel released 35 recommendations, including a $1.3-billion increase in the budgets of the three granting councils, the Canada Foundation for Innovation and related funding groups.

“There was concern in the spring that this report would be buried, hidden and never see light of day. I commissioned this report for a reason. I wanted to get the evidence and use that evidence as a path forward,” said Duncan, noting that she agrees with the majority of the report’s recommendations, particularly those related to governance and coordination.

Strengthening science

How the federal government will respond to the report’s call for more science funding was on the minds of everyone at this year’s CSPC. Even Duncan acknowledged “the elephant in the room”.

“My priorities are investing in investigator-led research and making sure we have sustainable, predictable funding for our labs and tools,” she said. “And I have real difficulty right now. I have world-renowned labs in Canada that don’t operate all year round. I want to fix that. It is a big ask. Is it something we can do in one budget, in one mandate? Look, the previous government dug a big hole; it’s going to take time to fix, but you have someone who is a champion for you.”

She described the funding boost to granting councils announced in Budget 2016 as a “down payment” and the “highest amount of new annual funding for discovery research in more than a decade”.

In addition to more science funding, Duncan said strengthening science in Canada also depends on having a more diverse, equitable and inclusive scientific community. The government made an important step towards this goal earlier in the day by announcing changes to the Canada Research Chairs program, including a cap on the renewal of Tier 1 chairs. The changes are designed to give mid-career researchers—particularly women, Indigenous peoples, visible minorities and persons with disabilities—a greater opportunity to become a chairholder.

“I don’t think I need to make the case to this group that when our research community includes people from diverse backgrounds with unique experiences, knowledge and perspectives, we are all one step closer to the next breakthrough idea or discovery. Broad perspectives breed great science,” said Duncan, who recalled the discrimination she experienced during her career as a scientist.

“I was told the reason I was getting paid in the bottom 10th percentile was because I was a woman. I was asked by a fellow faculty member during a staff meeting when I planned on getting pregnant. I was asked to choose how I wanted to be treated: as a woman or as a scientist.”

Another new initiative is the creation of the Canada Research Coordinating Committee, comprised of the presidents of the three granting councils and the deputy ministers from Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and Health Canada. The CRCC’s goal is to harmonize programs and policies of the federal granting councils and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

“This committee will look at how we fund multidisciplinary research better, how we fund multinational research better and multidisciplinary and multinational research better,” said Duncan.

Strengthening evidence-based decision making

The current federal government has committed to rebuild its capacity to deliver on evidence-based decision-making. Key to that pledge, said Duncan, has been the appointment of a new Chief Science Advisor (CSA). Dr. Mona Nemer’s job is to provide Duncan, the Prime Minister and Cabinet with independent scientific.

“It is then my job, as Minister of Science, to incorporate her findings into decisions made at the Cabinet table—decisions that affect the lives of Canadians,” said Duncan. “Science, in other words, is part of the mix of economic, social, regional, health, gender and diversity advice put forward by other members of Cabinet.”

The CSA is also assessing the merits of creating a network of departmental chief scientists, even in departments that aren’t science-based (e.g. foreign affairs). Duncan is also urging deputy ministers of all science-based departments to discuss how they can break down barriers and take a whole-of-government, multidisciplinary approach to complex issues such as Arctic research, artificial intelligence and climate change, as well as crises that require a fast policy response, like a pandemic.

“The work to build these bridges has already begun… The result? Stronger evidence that supports better decision making,” she said.

Strengthening the culture of curiosity

Duncan acknowledged that culture changes take time. That’s why efforts have to begin with young people, she stressed, with programs like Choose Science, PromoScience, Let’s Talk Science and Science Odyssey.

“I ask that you help me by encouraging the young people in your life to ask bold questions, challenge assumptions and find a way around any obstacle that may lie in their path.”

Duncan further challenged everyone in the room to “tell the story of how science helps us build a better world”.

“Show the people in your communities how science leads to new cancer treatments, advanced therapies for dementia, new technologies that fit in the palm of your hand and new horizons that have yet to be explored. If we work together, I am certain we will achieve our goals: a better society, a cleaner environment, a strong middle class and a better quality of life for everyone.”

The government’s science deliverables to date:

- Implementing changes to the Canada Research Chairs program, such as limiting renewals of the Tier 1 Chairs to two, 7-year terms, to increase diversity, equity and inclusiveness.

- Introducing new equity requirement in the Canada Excellence Research Chairs and Canada Research Chairs programs, and firm equity targets for universities.

- Establishing the Canada Research Coordinating Committee (CRCC) to harmonize programs and policies of the federal granting councils and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

- Appointing a Chief Science Advisor (CSA).

- Charging the CSA with assessing the merits of creating a network of departmental chief science advisors in government.

- Launching a Networks of Centres of Excellence competition that emphasizes multidisciplinary and multinational research initiatives.

- New investments in research and research infrastructure (e.g. $2 billion for the Post-Secondary Institutions Strategic Investment Fund; $554 million for CFI; $125 million for artificial intelligence).

- Reinstated the long-form census.

- Unmuzzled scientists.

- Reintroduced the University and College Academic Staff System survey and expanded it to include part-time faculty, as well as gender breakdowns.

Initiatives still pending

- Replacing the Science, Technology and Innovation Council with a more open and transparent body.

- Working with the Minister of Health to revise the Canadian Institutes of Health Research legislation to separate the function of the President and the Chair of the Governing Council.

- CRCC has been tasked with submitting a work plan within two months to map out how it will address issues such as:

- How Canada can increase its capacity to support international, multidisciplinary, risky and rapid-response research;

- How we can collectively advance efforts to support Canada’s strengths in strategic research areas; and

- What more can be done to increase equity and diversity and improve support for early-career researchers.

- Universities have until mid-December to submit Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Action Plans that will map out how they will meet their equity and diversity targets in the Canada Research Chairs program or risk having funding withdrawn.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Kirsty Duncan Keynore

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

One-on-One

Takeaways and recommendations:

Making Canada a beacon for science literacy and evidence-based decision making

Dr. Mona Nemer grew up during a time when women were generally discouraged from pursuing scientific or technical careers. When she learned that her all-girls school in Beirut, Lebanon didn’t offer a science curriculum, she successfully advocated for the high school to change its policy.

Now, as Canada’s second ever chief science advisor– and the first woman to hold the position – Dr. Nemer is championing efforts to make Canada a global beacon of scientific literacy and evidence-based decision making.

During recent meetings in Washington DC with officials at the National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the National Science Foundation, Dr. Nemer said she was struck by how many people were looking to Canada for leadership at a time when “fake news” too often trumps scientific fact.

“The United States, like other countries that have reached out to us, our European friends and the European Commission as well, see Canada as being on the right path. Given the international context, we have an opportunity to lead and people also expect us to lead… We need to act on this,” Dr. Nemer told conference delegates.

At the same time, when it comes to science and science policy, she said there is much Canada can learn from other countries, including the United States which is still our closest scientific collaborator.

“This is an opportunity to signal to our friends and collaborators abroad that Canada is open to collaboration and working with you on issues that are important to everyone. No one country can tackle issues like the environment, microbial drug resistance or the Syrian refugee. We have to work together.”

While there has been much talk in political and policy circles in recent years about the importance of evidence-based (or “evidence-informed”) decision making, Dr. Nemer said equal attention must be given to how science is undertaken. This means asking the right questions, gathering the right data in support of those questions, and coming to a conclusion based on the weight of the evidence.

“If you want to have good policy, if you want to have a good future for the country, then that’s the only way to go. If you don’t go this way, then you are going to be putting out policies that are inadequate and can do harm,” said Dr. Nemer, the former VP Research at the University of Ottawa and a distinguished medical researcher specializing on the mechanisms of heart failure and congenital heart diseases.

Dr. Nemer said she’s encouraged by the federal government’s emphasis on science and evidence. On her first day in the new position, she said Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told her, ‘I’ll take care of the politics. You take care of the science.’

Her office will provide the government with both technical and societal evidence that can be translated into various policy options. “There isn’t going to be one option … there would be options. These issues are not always black or white.”

She then reminded the audience of how independent her office will be when she said, “I get irritated when politicians alter the evidence in support of their decision making.”

The CSA’s job includes providing scientific advice to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, making recommendations to help ensure that government science is fully available and accessible to the public, and that federal scientists remain free to speak about their work.

“Another important part is that of convenor; engaging and really bringing together the intramural and extramural scientific community within Canada and also around world because science doesn’t stop at borders,” said Dr. Nemer “We don’t have walls on our borders but we have silos between us and that’s something we need to address.”

When it comes to intramural science, she said she plans in the near future to visit government labs, ADMs of science, chief scientists and individual scientists. “Intramural science is a big part of my mandate … I’m hoping it will be a close relationship and I’m here to help.”

At a time when the public’s mistrust of evidence and scientists is growing, a big priority for Dr. Nemer will be working with the larger scientific and policy communities to increase science literacy, including the public’s understanding of how science is done.

“We need to do it for the public. We need to do it for the country. It is essential for democracy that the public understand the content but also the methodology of science.”

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Mona Nemer Session

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Peter Severinson, Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences

Speakers: Lisa Kimmel, President and CEO, Edelman Canada; Mark Kingwell, Professor of Philosophy, University of Toronto; Rima Wilkes, President, Canadian Sociological Association

Moderator: Gabriel Miller, Executive Director, Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Historically, North Americans expected their relationship with government to be purely transactional: taxes to services. Things began to shift in the 1960s as the public began expecting government to better reflect their values.

- The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, a survey that looks at public trust in four key institutions – business, media, government and NGOs – found the following.

- To increase trust, organizations should improve on ethical business practices, treating employees well, and listening to customer feedback.

- Employees can be used to build trust: they are viewed as the most trusted people within an organization concerning the treatment of employees and customers, and on financial earnings and practices.

- Canadians are more likely to trust sources outside of established areas of authority than inside.

- Canada’s informed public trusts institutions, whereas the mass population distrusts institutions.

- Science literacy should be added to general literacy as required for democracy to work.

- There is no long a final authority for truth – a singular authority who holds the truth strikes us as untenable.

- Trust is the foundation of everything we do in a professional capacity: we need to trust strangers and institutions in order for societies to function.

- Who can afford to trust? In order to trust, a person takes a risk. A poor person, for example, has more to lose in trusting: to trust isn’t necessarily the best thing for certain individuals.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Big Thinking Panel

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Speakers: Michael Jenkin, retired civil servant and former SCC staffer; Janet Halliwell, final SCC president and chairman, Principal, JE Halliwell Associates Inc.; Jeff Kinder, Director of Innovation Lab, Institute on Governance; Paul Dufour, Fellow and Adjunct Professor, Institute for Science, Society and Policy, University of Ottawa

Takeaways and recommendations:

One of Canada’s most renowned government science policy organizations is being revived, at least in book form. Co-editors Paul Dufour and Jeff Kinder chose the Canadian Science Policy Conference to launch their new book on the Science Council of Canada (SCC), an arm’s length think tank that operated from 1966 to 1992.

A Lantern on the Bow: A History of the Science Council of Canada is in the final stages of compilation with a publication date slated for early 2018. It contains chapters contributed by 13 science policy experts, many of whom worked at the SCC. The book details the impressive body of work produced by the SCC and the forward-looking advice it provided to government, complete with recommendations.

Much of the work conducted by the SCC focused on industrial and technology policy, more commonly referred to these days as innovation policy. The major conclusions made by the SCC over the years don’t seem all that revolutionary or controversial today but at the time they represented a major departure from the conventional wisdom and science policy of the day.

“While this is a book about looking back, it’s also a book about looking forward in terms of what we’ve learned from our current experiments in science and science policy,” says co-editor and contributor Paul Dufour. “I think the Science Council of Canada contributed greatly, particularly around the current science and innovation policy debates we’re having today.”

For example, several SCC reports reinforced the contention – which was new at the time – that the emergence of technologically sophisticated commercial activity was key to export success, stable growth and high-paying jobs. As such, it should be the primary focus of any industrial policy.

“From the middle 1970s through to the early 1980s, Canada and most of the industrialized world were going through a crisis in economic policy,” says Michael Jenkin, a former staffer at the SCC. “That was where the Science Council’s approach became both controversial and very different. It took as its departure point how to get inside that black box called technology and it did it from a very different, multidisciplinary, perspective…It drew on a lot of the work done in Europe in the sixties … how the evolution of technology had changed the nature of how industries performed.”

Janet Halliwell, the SCC’s last president, noted that the work of the SCC took five major trajectories: mapping and analyzing major scientific disciplines; major science projects; relationships and interactions among scientific activities and national needs; the application of science and technology to specific sectors of the Canadian economy and technology; and industrial and innovation policy.

“In all our major reports on large-scale initiatives was that central theme of aligning our investments with social and economic benefit for Canadians, and how you achieve that dynamic balance. We were talking about things like oceans, water, space, the upper atmosphere (and) we positioned these in the context of national goals … They were somewhat embryonic at the time but we really tried to take a stand on that … focused on the science, engineering and technology dimensions.”

Because all SCC reports included recommendations, Dufour said that meant “you were going to get into trouble on occasion”. Controversy often followed some of its recommendations which stimulated debate across the country. The landscape for science policy began to change in the 1980s when government developed in-house policy capacity which led to an atmosphere of tension and competition, eventually leading to the closure of the SCC, ostensibly as a cost cutting measure.

“I do have a fond memory and passion for what an organization like the science council could do, and how it’s pan-Canadian, independent nature allowed it to address emerging issues which I think other organizations struggle to get at,” said Dufour. “At some point, governments hate getting advice that’s independent, sometimes when it clashes with their own agenda, platform and ideology, so you have to be extremely carefully about the context in which you’re providing advice. That’s the lesson I learned.”

Dufour noted that many of the more than 400 reports produced by the SCC have been digitized. They are available at www.artsites.uottawa.ca/sca/en/science-council-of-canada.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Book Launch

Bridging the Divide: Incorporating Up-to-date Research Findings and Social Shifts into Public Policy

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Sally Rutherford, Canadian Association for Graduate Studies

Speakers: David Bailey, President and CEO, Genome Alberta; Ronald-Frans Melchers

Professor of Criminology, University of Ottawa; Eric Montpetit, Professor, Political Science Department, Université de Montréal; Bonnie Schmidt, Founder and President, Let’s Talk Science

Moderator: Brenda Brouwer, Vice Provost and Dean, School of Graduate Studies, Queen’s University

Takeaways and recommendations:

- We are at a tipping point in making the case for science as a driver of economic growth and societal well-being.

Increase effective communication

- Scientists need to communicate better with the public to increase the credibility of science, break down barriers/perception of academics as “elite”, and spark innovation.

- Scientists need to evaluate and understand the risks and benefits of speaking out. What is your goal in speaking out, who is the audience you’re trying to reach and how do you effectively communicate with that audience.

- Scientists should be trained to be better communicators in university. Some level of policy knowledge should also be mandatory.

- Common language supports shared understanding, and both policymakers and scientists are responsible for ensuring they use language that is accessible and properly understood by the other party. There are programs that can help with this process and these should be supported.

Understand the role of scientists in the policy process

- The expectation of the role that scientists should play in creating policy is often too high; scientific evidence is just one input into the policy process.

- Scientists are not necessarily experts in the policy process and they are not (and should not be) involved in the actual decision-making process.

- Policymakers need to listen to and respect scientists, but ultimately the responsibility for the decision falls on them. They should not blame scientists if a bad decision is made.

- Policymakers and scientists often have little knowledge or understanding of the policy creation processes. Connect the few experts in this area to scientists and policymakers so they can help ensure that science is effectively used to improve policy, and facilitate an understanding of each other’s roles.

Build a skilled generation

- There are many existing initiatives that help improve the public’s knowledge of science. These initiatives should focus on building a skilled and science-literate population – not just increasing the number of people who become engineers.

- Young people who are more science literate are more understanding and respectful of science by the time they enter the workforce.

- More policymakers are recognizing the importance of supporting youth STEM programs. Initiatives at the K-12 levels have a stronger impact on the innovation economy than those at the post-secondary level.

- There is no national ministry of education, so it is difficult to talk about education at the national level. Canada 2067 is working to create that vision. This national initiative brings together educators, businesses, governments, community groups, parents and youth to evolve Canada’s education model by enhancing student exposure and access to STEM disciplines across all levels and areas of learning.

Advice for scientists

- Although some advice can be given in crucial moments for policy creation, if you want to influence policy over the long-term you need a long-term view – it can be years before any change happens.

- Scientists are not usually experts in creating policy or public services; as such they need to listen to and respect the experience of policymakers.

- Scientists should get more involved in policy-related matters to build their understanding of the language and processes.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Bridging the Divide

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Leigh Paulseth, Ryerson University

Speakers: Emily Agard, Director, SciXchange, Ryerson University; Stephanie MacQuarrie, Associate Professor of Organic Chemistry, Cape Breton University; Nadia Octave, Medical Physicist at Centre-Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec, Université Laval; Leigh Paulseth, Enrichment & Outreach Coordinator, Ryerson University

Moderator: Imogen Coe, Professor; Dean, Faculty of Science, Ryerson University

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) policies should be evidence-based and create effective change – as opposed to existing merely to give the people who enacted them a good feeling.

- Many STEM-engagement programs reach children who are already involved; e.g. those who have already expressed an interest in STEM, have supportive parents, live in cities, are wealthier, etc.

- To be effective and to reach a broader audience, science-engagement strategies must be grounded in the community – both physically and in terms of relating back to issues that are important to that community.

- Soapbox Science is an award-winning science outreach program, created in the U.K. in 2011, which promotes women in science; e.g. by bringing female scientists to the streets to talk to the public about science. (Ryerson’s Faculty of Science launched the first Soapbox Science event in North America in May 2017.)

- The Soapbox Science program is an easy, inclusive, affordable and proven method that challenges stereotypes of science and scientists. It also normalizes the idea that scientists come from diverse backgrounds while promoting scientific research and literacy.

- Providing opportunities for female scientists to have their voices heard can be a significant and impactful experience for the scientist as well as public participants.

- The program is portable and easily adaptable to various regions.

- It is a useful tool to develop communication skills for scientists.

- Proper training for scientists before they participate in Soapbox Science is essential; organizers should use the expertise of other professionals like improv and theatre colleagues, communication experts, etc.

- The UK Soapbox group has many materials that organizers here can use and adapt.

- Institutions that get involved should be committed to engaging for the long term; it’s not intended for use as a one-time event.

- Soapbox Science is usually spearheaded by post-secondary institutions, but could easily be adapted for use by government departments with government scientists.

- Soapbox presents a tremendous opportunity to join a global movement, something Canada is too often slow to do.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Shifting Gender Norms in Science

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Angela Behboodi, Hoffmann-La Roche Limited

Speakers: Kym Boycott, Leader, Care4Rare Canada and Rare Diseases Models and Mechanisms networks; Susan Marlin, CEO, Clinical Trials Ontario; William McKellin, Medical Anthropologist, University of British Columbia; Durhane Wong-Rieger, CEO, Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders

Moderator: Lawrence Korngut, Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary

Takeaways and recommendations:

Policy considerations

- Canada needs a national data infrastructure for rare disease research that is cloud based and uses internationally recognized data standards such as those developed by theGlobal Alliance for Genomics and Health. Such an infrastructure should include standard operating procedures, harmonized agreements between provinces (i.e. for sharing patient data) and a governance framework which includes terms for data access.

- Proposed changes to Patented Medicines Regulations may delay new drugs and hinder life science investments.

- Canada needs an effective policy for moving drugs from off-label to on-label; this would also allow for reimbursement of these drugs.

- Canada needs a fully developed regulatory framework for orphan drugs that provides incentives for R&D, similar to U.S. (Orphan Drug Act of 1983) and Europe. This would create a harmonized system that allows companies to apply simultaneously to Canada, U.S. and Europe for an orphan drug designation.

- Canada needs to take a life cycle approach to drug development, access, monitoring and feedback—one that involves patients and families.

- Canada needs a policy that would provide patients with early access to drugs not yet approved here.

- Canada would benefit from uniformed newborn screening of diseases.

Research considerations

- The clinical community has come together with a common vision: to enable all people living with a rare disease to receive accurate diagnosis within a year; next generation sequencing reduces the time and cost of diagnosis by simultaneously examining many to all genes at once.

- Achieving that vision will require fundamental changes to the way science is conducted, shared and applied to the care of patients with rare diseases (e.g. FORGE Canada and Care4Rare Canada research consortia)

- Canada has a strong collaborative model for rare disease research and a strong clinical trials environment.

- Opportunities include: increase efficiencies of clinical trials (e.g. reduce study start up); improve patient/public engagement with trials; collaborate across Canada to improve performance

- Micro-grants (about $3500 each), peer-reviewed by scientists and parents, can help establish the relevance of a particular research project.

- Fund more clinician-driven research. This would allow for off-label testing, and the development of innovative treatment protocols based on a particular patient.

- There is a need for a national centre of research excellence to bring all the stakeholders together to address research gaps.

Patient/family considerations

- Consider the importance of patient- and family-reported outcomes (“Personally Meaningful Outcomes”).

- Breakdown silos (e.g. research, health, education) that segregate families by the disease; instead, respond to shared experiences that cut across disease types and research disciplines.

- Almost every rare disease policy was the result of patient group advocacy and rare disease groups are increasingly taking the lead in funding and designing research programs.

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Jesse Rogerson, Canada Aviation Space Museum and Stephanie Deschenes, Canadian Association of Science Centres

Speakers: Chantal Barriault, Director, Science Communication Graduate Program, Laurentian University and Science North; Stephanie Deschenes, Executive Director, Canadian Association of Science Centres; Marianne Mader, Managing Director, Royal Ontario Museum; Rachel Ward-Maxwell, Researcher-Programmer, Astronomy and Space Sciences

Moderator: Jesse Rogerson, Science Advisor, Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Takeaways and recommendations:

- The more the public is taught the correct answers, the more they will agree with ‘scientific findings.’ i.e., “you just don’t know enough, let me teach you” doesn’t work. An outcome of their understanding is they will be more interested in helping fund science. But let’s focus on the deficit model as the ‘lack of understanding’ being the reason for disagreeing with a science-based conclusion.

- Canadians are interested in science, and see value in science.

- Polarizing ideas are associated with values, and those associated to a social group

- Separate knowledge and identity – who we are influences how we interpret the information we receive.

- Does the information fit with what I know and believe? If not, do I need to protect my personal interests, beliefs and values?

- Faced with information incongruent with values, people often look to trusted sources to evaluate that information.

- The echo chamber forms because trusted sources tend to be people who hold similar values to our own.

- Science communication is less about the facts and more about connecting.

- What can we agree on and where do we build from there?

- Museums and science centres are partnering with researchers to give visitors the opportunity to participate with scientists in the process of research.

- Science centres, scientists, and educational institutions are seen as trusted sources for accurate, fact-based information: they are viewed as not having a hidden agenda.

- Museums and science centres are safe spaces, where respectful, difficult conversations can happen – “We’re not going to convince everybody; yet we can still respect everybody.”

- A museum/sci centre is a much more accessible location to interact with scientists, as opposed to a government or university lab. You simply can’t visit those places. This makes it natural to partner with Museums/Science Centres, we have your audiences, you have the story to tell, let us help.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Changing Perceptions

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

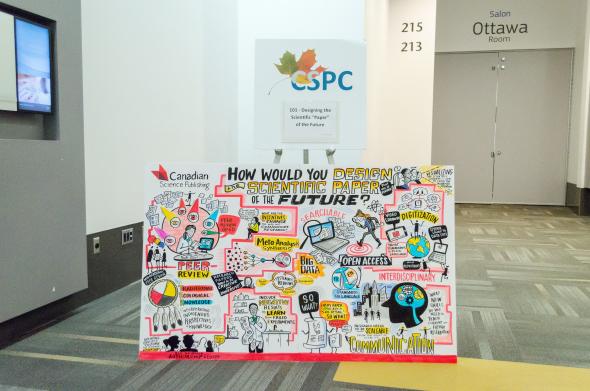

Organized by: Rebecca Ross, Canadian Science Publishing

Speakers: Steven Cooke, Professor, Canada Research Chair at Carleton University; Maria DeRosa, Professor, Chemistry Department at Carleton University; Brian Owens, Freelance writer and journalist, Nature, New Scientist, Science, and the Canadian Medical Association Journal; Chelsea Rochman, Assistant Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto, Laura Coristine, Scientist, Conservation Biologist and Liber Ero Postdoctoral Fellow, University of British Columbia

Moderator: Laura Coristine, Scientist, Conservation Biologist and Liber Ero Postdoctoral Fellow, University of British Columbia

Figure credit is to: Liisa Sorsa, Thinklink Graphics

Takeaways and recommendations:

Engaging with a non-scientific audience

- More publicly funded science is migrating to open access journals, but that doesn’t ensure it will be widely read or understood. How can we make our papers more accessible?

- Prioritizing vetted science and protecting and instilling trust in scholarly research is more important than ever in a world where fake news and predatory publishing practices contribute to a public that does not always trust evidence or scientists.

- Science increasingly addresses time-sensitive issues (climate change, technological advances, etc). Information around this research needs to be communicated in a variety of ways (e.g. op-ed columns, media interviews, blog posts, policy briefings, presentations to government committees as well as the more traditional academic publication) in order to inform a variety of audiences ranging from policy-makers to general public and scientists.

- More funding is needed for systematic reviews as policymakers don’t have time to read an entire body of knowledge (i.e., numerous individual scientific papers).

- The most important information is often found in the methods, results and figures sections of a scientific paper, but they are usually the hardest parts for a lay person to understand. Can they be presented in a more accessible way? “Science literacy has to be appreciation for science as well as the scientific method.”

- Write scientific papers in an active, not passive, voice.

Where are the incentives to change?

- What is the researcher’s incentive to communicate their results in different ways?

- Think of impact beyond the “impact factor”. The current scientific paper is the “currency” that drives tenure and promotion in academia. But is there a way to reward and measure other impacts or outputs, especially research that is used to make evidence-based decisions that contribute to an informed electorate, a scientific literate society and real-world solutions?

- Established researchers should lead the charge in testing new approaches to communicating scientific results.

- All stakeholders must come together to help develop a sustainable business model for open access.

Ensuring scientific excellence

- Scientists will continue to need traditional scientific papers as a way to share findings with other scientists.

- How can peer review be applied to non-traditional forms of “publishing” (e.g. story board, blog, video diary), and can core science messages be maintained in these new communications tools? What is the business case for adding additional communication features to scientific journals?

- Package information in ways that make the research reproducible, and (ii) increase science capacity for attaining new research knowledge (e.g., GitHub, Open Science Framework, living papers, publication of non-confirmatory results)

What a future scientific paper should include:

- Instead of reinventing the scientific paper, supplement the current format with information that is easier for a lay public to understand. (e.g. short video clips and visuals that make complex data easier to understand.)

- As science becomes more interdisciplinary and connects with a broader audience there is a need for the scientific paper to seamlessly connect with concepts, figures, data, video and other formats that might tell a science story more people can understand and utilize.

- Use graphic designers to better visualize data in papers.

- Consider writing abstracts for scientific papers in the inverted pyramid style, as is done in journalism where the most important information (“why the research matters”) appears up top.

- There should be a clearer connection between a scientific paper and all the outputs linked to it (e.g., datasets, multimedia, social media, news coverage, past work and new papers that build on the research) author’s previous research papers and new papers that build on this research.

- Make papers more accessible to young people to encourage an interest in STEM disciplines.

- Include a lay summary. But if the author doesn’t provide this, who will and who will pay – research granting councils? Journal publishers, such as those affiliated with professional scientific associations or bodies, may be better equipped to provide this service, and academic faculties could hire science communicators.

- Translate supplemental information into different languages to reach specific lay audiences.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Scientific “Paper” of the Future

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Kirsten Vanstone, Royal Canadian Institute for Science and Reinhart Reithmeier, Professor, University of Toronto

Speakers: Chantal Barriault, Director, Science Communication Graduate Program, Laurentian University and Science North; Maurice Bitran, CEO, Ontario Science Centre; Kelly Bronson, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa; Marc LePage, President and CEO, Genome Canada

Moderator: Ivan Semeniuk, Science Reporter, The Globe and Mail

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Canadians are engaged and informed about science, and have positive attitudes relative to citizens in other countries.

- Many Canadians struggle to explain fundamental scientific concepts.

- Science centres in Canada can be leveraged to communicate on a set of scientific areas, creating a cohesive picture of specific scientific areas and capitalizing on public trust in researchers, science centres, and educational institutions.

- The precious commodity is no longer knowledge, but the ability to sort through information and the passion to follow a certain route.

- Methodological diversity, leading to conflicting expert opinions, may undermine the role of science in a policy matter.

- Uncertainties inherent in scientific results may lead the public to lose trust.

- The public has an important role in asking tough questions of scientists.

- Decision-making within institutions should bring the public into discussions early on, especially about public-funded innovations or technologies.

- Canada’s science culture is strengthened by the graduate training of scientists, empowering them to act as members of the public.

- The role of science in people’s lives and the construction of their beliefs and values are influenced increasingly by social media and their social and cultural identity.

- A research gap exists in science media, on what’s covered and how it compares to other countries.

- There is a gap in media coverage of Canadian science. Who will cover Canadian science and in an independent way?

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Science Culture

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Tina McDivitt, Spindle

Speakers: Gordon Kurtenbach, Head of Autodesk Research, Autodesk; Amy Lang, Director of Patient, Caregiver and Public Engagement, Health Quality Ontario; Donald Stuss, Founding Director, Baycrest’s Rotman Research Institute founding President and Scientific Director, Ontario Brain institute

Moderator: Mark J. Poznansky, President and CEO, Ontario Genomics

Takeaways and recommendations:

Convergence and trans-disciplinary research

- Trans-disciplinary research is emerging as a result of people being trained in multiple disciplines, and the convergence of engineering, life sciences and physical sciences.

- Public, professional and commercial stakeholders are needed to define the scale, scope and foci of research.

- Support should be provided to areas of research where Canada can have a competitive advantage.

Improving clinical diagnosis

- Diagnoses need to be made in terms of clinical sub-syndromes: a systems approach, which will ensure the use of correct target candidates in clinical trials and improve their efficacy.

- Put the patient in the centre: integrate all aspects that are relevant to maximizing patient benefits.

- Embed research into clinical practice and embed commercialization into research.

Technological platforms

- Bridging technology platforms allows the application of new scientific knowledge to scientific and industrial processes.

- It is critical to support interdisciplinary connections and make working with disparate datasets easy.

- Platforms allow for a systems approach, which is needed to address complex global challenges.

Engaging patients and caregivers in healthcare policy

- Effectively engaging patients and their caregivers can have a positive impact on many aspects of the patient’s healthcare.

- Patient and public participation in health policy, service design, and governance can lead to better-informed and more sustainable decisions and programs.

- Engaging patients can change the way different kinds of evidence are weighted in decision-making for health policy.

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Jennifer Sokol, Polar Knowledge Canada

Speakers: Jean-Sébastien Moore, Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, Université Laval; Marie-Eve Neron, Director of Climate Change and Clean Energy, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Angela Nuliayok Rudolph, Master’s Student, Arctic and Northern Studies program, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Moderator: David J. Scott, President and CEO, Polar Knowledge Canada

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Integrating indigenous knowledge into a scientific program can play a major role in its success:

- The Arctic Char Traditional Knowledge Study used indigenous knowledge to successfully determine the path of migrating fish.

- The elder-youth knowledge exchange camp (part of the research program supported the community’s exchange of information from the elders to the youth) helped the community participate in and inform the research.

- Incentives and training should be improved to support scientists in involving indigenous communities in research programs.

- Scientists need to better understand the power of the relationship between the communities and the resources they depend on – those resources are the reason why communities were established in those places.

- People want to define indigenous knowledge and how they can use it, but a simple definition is hard to come by.

- Indigenous traditional knowledge is unique to each community.

- Direct translations can lead to inadequate interpretations of indigenous language and terms.

- To use indigenous knowledge in research programs, trust must be established and youth and elders should be engaged: this is a way for youth to be valued and for elders to transmit information, which helps to strength communities.

- A paradigm shift is needed: the best results occur when communities identify their needs and partner with scientists to find answers.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Indigenous and Western Science

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Council of Canadian Academies

Krista Connell, Chief Executive Officer, Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation; Jeff Kinder, Director, Innovation Lab, Institute on Governance; Rémi Quirion, Chief Scientists of Quebec; David Schwarz, Senior Director, Science Policy & Evaluation, Alberta Economic Development & Trade.

Moderator: Eric Meslin, President and CEO, Council of Canadian Academies

Takeaways and recommendations:

- The provincial role in science policy and investment is often ignored at the federal level, resulting in a disjointed and fractured system across Canada.

- Provincial science policies can bring clarity to provincial research priorities and effectively leverage federal science policy, according to a recent report from the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA) (Science Policy: Considerations for Subnational Governments).

- Quebec science policy is anchored around the position of the Chief Scientist who has a good network to assist with coordination and dissemination.

- The CCA report offers an opportunity to discuss science and technology at the subnational level which has not taken place in 30 years.

- Through the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (FRQ), Quebec has successfully advocated for funding increases to the provincial granting councils. Quebec scientists are also very competitive at the federal level.

- The Alberta government, which commissioned the CCA report, has recognized that there are direct economic benefits stemming from support for fundamental research and has completed a needs assessment and outcomes map of the science system.

- The CCA report is allowing Alberta to further its science policy considerations and engagment, thus allowing the province to identify and invest in key priority areas.

- Provincial leverage of federal science investment is a complicated dance that requires carefully conceived coordination.

- Federal-provincial coordination is challenged by different visions of success, tensions between researcher-driven and priority-driven research, and differing perspectives on the function and management of the research enterprise.

- Matching requirements of federal science programs is a major provincial concern. If not matched, federal money is left on the table.

- Subnational science policy should be developed and deployed to help prepare for the imminent arrival of key disruptive technologies.

- Provincial science policy must also include discussion and interaction with cities where the biggest impact of research and new technologies will be felt.

- Science at the federal, provincial and municipal levels are all part of the same ecosystem. It’s time to start acting like one.

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Sasha Wood, New Brunswick Social Policy Research Network and David Phipps, York University

Speakers: Marcelo Bravo, Liu Institute for Global Issues; Cathy Malcolm Edwards, Managing Director, 1125@Carleton, Carleton University; Rodney Ghali, Assistant Secretary of the Innovation Hub, Privy Council Office; Bill MacKenzie, Director of Strategic Partnerships, New Brunswick Social Policy Research Network; Matthew McKean, Associate Director of Education, Conference Board of Canada; Nick Scott, Executive Director, Open Government and Innovation, Government of New Brunswick

Moderator: Dr. Robert Haché, Vice-President Research and Innovation, York University

Takeaways and recommendations:

Why we need social policy research networks and knowledge mobilization hubs

- The problems facing society and government are increasingly complex. “Quick fix” solutions often address symptoms but not causes, and may even add to the complexity of future issues.

- No one person, or one government, can solve these complex problems. Instead, you need diverse teams with a variety of perspectives to generate the evidence that supports evidence-informed solutions.

- It is helpful to have a neutral third party that facilitates these connections.

- The New Brunswick Social Policy Research Network (NBSPRN) is one such convener. It brings together civil society, informed citizens, policy makers and researchers to have these broader conversations. They also keep an eye on the evolving landscape to ensure the relevancy of their focus/advice, and work with researchers to help them build partnerships.

- NBSPRN wants to develop a policy “skunkworks” for government. Designed to innovate quickly with minimal with minimal management constraints, skunkworks support innovation in policy, take more risks and allow policymakers to do things they cannot in the usual policy process. The structure also brings in a greater diversity of perspectives.

Increasing evidence-based policy development

- Government needs to be explicit and clear about its challenges so organizations like NBSPRN can connect them with the right people. Take the time to frame the challenge in a way that is useful and achievable.

- Policymakers are busy and have a lot of pressure; evidence therefore has to be presented to them in an organized, clear and understandable way.

- The process needs knowledge brokers who can successful navigate between academia and different partners who understand all the sides.

- Knowledge mobilization hubs seek to be these brokers, which also provide a one-stop hub for people wanting to partner with academia.

- The current climate presents an opportunity for the federal government to accelerate these partnership models so they are widely institutionalized.

Advice for knowledge mobilization hubs

- Previously-existing relationships are essential for meaningful connections and discussions on policy issues.

- An ad-hoc or transactional approach to relationship building is often ineffective. Instead, focus on a systematic approach that builds an ecosystem, facilitates timely connections and allows for long-term, sustained relationships between individuals and between institutions.

- Any stakeholders should be involved in the problem from the beginning so they are invested in the knowledge translation and the outcomes.

- It is essential to bring diversity and ‘unusual suspects’ to the table when designing solutions for social impact, designing policy or creating a research project. This networked approach ensures a broader systems-level view that is more likely to create an effective and relevant solution.

- It is important to consider what projects are not suitable for academics; a successful input requires them to have time and space to do credible job.

- Maintain a stable of academics that are on call for projects, particularly short term ones. Ensure you know their strengths and interests.

- To stay relevant when governments change, policymakers should focus on specific projects and provide rigorous, fearless advice. You are a public servant. Do not tie yourself to the political machine.

Breaking down the silos

- More effort is needed to break down the silos between industry, academia and government, as well as cross-sectorial and cross-departmental in academia and in government.

- Ensure everyone understands the values that other sectors/departments bring, as well as their different tools, languages and relative strengths.

- Look for alignment – get people engaged with and working on a common problem.

- Have one person at the table who is open about the challenges different parties face in working together.

Developing skills for knowledge mobilization

- True impact requires people with the social, communications and knowledge mobilization skills to translate research into results. This includes experience in building strong partnerships and tailoring solutions to meet he needs of different groups.

- Knowledge mobilization hubs and institutions need to develop capacity skills in knowledge mobilization for students and faculty.

- Within faculties where there is less support for knowledge translation, institutions should identify the few who are interested and support them with training and professional development.

- Job-ready graduates need 21st skills for employability (as defined by the World Economic Forum), including: empathy, ability to look at and address complex problems, and capacity for leadership.

Grad students and knowledge mobilization

- Don’t only focus on the academic “superstars.” The evidence indicates that grad students play a crucial role in knowledge mobilization and more is needed to support and recognize this.

- Knowledge mobilization is a valuable and employable skill.

- Institutions should create space for students to acquire knowledge mobilization skills, as well as incentives and structures that support this activity.

- Students need opportunities to act as knowledge brokers independent of their research.

The changing face of knowledge mobilization

- The evolution of technology is enabling researchers and policymakers to get data directly from citizens instead of going through elaborate and time-intensive processes which accelerate the process for gathering, synthesizing and processing information.

- It is important to have trusted relationships/partnerships already developed so that policymakers can get advice quickly when a policy crisis arises. (e.g. something blowing up on Twitter)

- While academia needs to adapt to provide decisions makers with a quality analysis in a short-term cycle, it should not be at the expense of the long-term focus.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Mobilizing Research

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized and Moderated by: Viviana Fernandez, Assistant Director, Human Rights Research and Education Centre (University of Ottawa) and Steering Committee member of the Scholars at Risk Canada Section.

Speakers: Fayyaz Baqir, University of McGill; Philip Landon, VP Governance and Programs, Universities Canada; Joyce Pisarello, Senior Program Officer, Membership and Outreach, Scholars at Risk

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Canadian academic institutions have long seen themselves as open to global talents and as open and inclusive spaces.

- Recent international events, particularly in the U.S., have resulted in an increase in faculty and students looking to come to Canada (enrollment in the last year was up 10% for international students).

- It is important for Canada to continue to act on its commitment to be a sanctuary and safe space for international researchers, especially refugee scholars.

- The recent Action plan on equity, diversity and inclusion from Universities Canada is a step in the right direction, especially as it includes specific action-based commitments.

- Three other good examples of Canadian actions are:

- The globally unique ability of Canadian students to sponsor refugee students;

- The Universities Canada statement opposing the U.S. travel ban, and

- The Borderless Higher Education for Refugees project

- Specific support for refugee scholars should include help with networking in the new community, as well as allowing scholars to restart or resume their work where appropriate, circulating their CV, and ensuring there is support for scholars who wish to return to their home country when the threat is lessened or eliminated.

- Continued support for organizations like Scholars at Risk is vital.

- More Canadian academic institutions should join the Scholars at Risk Network. To help enable this, there needs to be more individual champions for the program within institutions. Interested individuals or institutions should contact the SAR Canada Section.

- Scholars at Risk’s open source project which tracks academic freedom globally needs continuous help from scholars to help with data aggregation.

- Today’s conflicts are connected to global issues, and as such, the Canadian government and academic institutions should constantly evaluate their role in influencing these issues.

- They should also consider the impact of these global issues within their own communities (e.g. when people have families or networks in the affected areas).

- Media has to play the role of world conscious by exercising due diligence.

- Academia needs to conduct research to separate facts from alt facts.

- All, including government, need to insist on accountability for violation of constitutional governance norms.

- Academic freedom and freedom of speech are the bedrocks of Canadian universities. It is important to allow difficult dialogue without encouraging the proliferation of racism and other hateful speech.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Science at Risk

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Urs Obrist, Embassy of Switzerland

Speakers: Shiho Fujiwara, First Secretary, Embassy of Japan in Canada; Urs Obrist, Senior Science and Technology Counsellor, Embassy of Switzerland; Antoine Rauzy, Science and Higher Education Attaché, Embassy of France; Marcus Stadthaus, First Secretary, Sustainable Development, Energy, Embassy of Germany

Moderator: Mehrdad Hariri, Founder, CEO & President, Canadian Science Policy Centre

Takeaways and recommendations:

Japan

- In Japan, S&T diplomacy is supported by the Science and Technology Basic Law of 1995; one of its objectives is to “contribute to the progress of S&T globally in the world and the sustainable development of human society”.

- Japan established an S&T advisor in 2015: provides advice to the Foreign Minister and relevant departments on the utilization of S&T in various foreign policy makings. It also reinforces networking among S&T advisors and scientists/academics.

- The S&T advisor’s first policy, released in 1996, stressed the importance of diplomacy for S&T but there was no mention of S&T for diplomacy; the term “S&T diplomacy” (which includes both S&T for diplomacy and diplomacy for S&T) was incorporated into policy in 2011.

- Japan has bilateral S&T agreements with 47 countries and institutions; the one with Canada has been in place since 1986.

- Japan also participates in multilateral meetings that involve S&T: recent examples include the G7 S&T Ministers’ Meeting (agreed to cooperate on global health) and the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (stressed importance of S&T promotion).

- It is important to have common goals when collaborating bilaterally or multilaterally.

- Future opportunities for S&T diplomacy include:

- Working together to solve global programs (i.e. support data/evidence-based policy decisions and the UN Sustainable Development Goals).

- Deepening relations between partner countries by promoting opportunities for collaboration (e.g. S&T Research Partnership for Sustainable Development – SATREPS) and strengthening networks among scientists.

Switzerland

- Switzerland has 20 S&T counsellors around the world and 5 Swissnex offices (the first Swissnex office opened in Boston 17 years ago)

- The Swissnex model’s strengths include:

- Flexible outreach mechanisms (i.e. the network includes main offices and smaller satellite offices globally, as well as mobile offices)

- A mechanism for supporting Swiss education, research and innovation institutions with their internationalization endeavours.

- Mixed funding and flexible partnerships (public, private, academia, foundations, local partners).

- Open collaboration.

- Switzerland’s biggest natural resource is its “grey matter”, thus the importance of participating in multinational organizations like CERN and the Arctic Council.

- Switzerland has been ranked world’s leading innovator for 7 years in a row according to the INSEAD/WIPO Global Innovation Index and, like Canada, has 7 universities ranked in the top 200. This ambition for academic excellence and the structural similarities with multilingualism and federalism are a good basis for enhanced scientific relations between the two countries.

- Two government departments are directly involved in science diplomacy: the FDEAER, which oversees the State Secretariat for Education Research and Innovation, and the FDFA (where embassies and consulates have scientific counsellors who work for foreign affairs department).

- Flexibility is key to Swiss scientific diplomacy.

- Main tasks for science diplomacy include:

- Monitoring and anticipating developments in science policy.

- Establishing and maintaining contacts.

- Organizing events and multidisciplinary activities.

- Stimulating and supporting cooperation projects in the areas of university or industry research (with an emphasis on priority areas for Switzerland).

- Promotion of Switzerland as a cooperation partner in STI.

- Support of internationalization efforts of universities, start-ups and spin-offs.

France

- Several bilateral agreements provide a foundation for cooperation between Canada and France, including: the Enhanced Cooperation Agenda; the Declaration on Innovation; the France-Canada Research Fund; and the Youth Mobility Agreement.

- The French diplomatic and scientific network includes: ministries of foreign affairs and higher education and research; 80 scientific advisors or attachés; foreign offices of major research institutions (e.g. CNRS, Pasteur Institutes); and researchers (e.g. international labs of major research organizations; R&D labs of large French companies; foreign-based branches of French universities).

- France built the world’s second international network for scientific and cultural cooperation: its two main objectives are excellence and influence.

- Priorities for supporting French science’s excellence at the international level:

- The international deployment of the national research and innovation strategy.

- The organization of French research abroad.

- The attractiveness of France for foreign researchers.

- The intelligibility of the French research structure.

- The participation of French researchers in very large research infrastructures, and promoting the installation of such infrastructures in France.

- The internationalization of French social and human sciences.

- France and Canada have strong bilateral S&T linkages between institutions of higher learning, research clusters and centres of excellence.

- The France-Canada Research Fund, an agreement between the Embassy of France in Canada and Canadian universities, promotes and develops scientific and academic exchanges, particularly among young researchers.

- There is a natural interplay between traditional diplomacy and science on global issues such as climate change, sustainable development, health, biodiversity, cybersecurity and energy.

- It is important to maintain S&T links between countries that have difficult relations.

- Diplomacy also means participating in policy development through involvement in international scientific and cultural organizations, such as: the European Space Agency, WHO, UNESCO, Arctic Council, CERN and the International Space Station.

- The “French Touch” in science diplomacy includes: core values (e.g. freedom of research and the scientific approach); promotion of gender equality, diversity and accessibility; study of human and social sciences; MOPGA initiative (resident permit for scientists).

Germany

- 50 German embassies and consulates have science departments; half of those S&T attachés are diplomats; the other half are from Germany’s ministry of education and research.

- Centres of excellence and innovation houses have been established around the world (none in Canada yet).

- Germany’s underlying principles of its approach:

- Freedom of science: is enshrined in German’s constitution. Germany has only one funding institution for science (DFG) and its only criteria is academic excellence. Scientists decide where to spend money; there is no earmarking from the political level.

- Attracting and advancing the brightest minds.

- Institutional architecture for broad-based scientific enquiry.

- Internationalization: Germany has implemented an internationalization strategy (have more than 300,000 international students in Germany).

- Strong science culture: includes science literacy.

- Germany’s non-university research organizations support the full spectrum of research, from fundamental to applied.

- 68% of Germany’s R&D comes from industry, with the remainder coming from government and universities. (Germany has doubled its investments in R&D since 2005.)

- Canada is the #1 partner in the DFG; Canada hosts 11 out of the DFG’s 39 international research training groups. (e.g. NSERC CREATE program)

- DAAD: Awards 1000 scholarships for Canada-German academic exchanges annually; DAAD has an information centre in Toronto.

- The Germany embassy in Canada assists in hosting science delegations – to Canada from Germany, and from Canada to Germany. Its role is to facilitate, inform and connect.

- The German embassy also hosts its own events in Canada (e.g. Future of Energy, Future of Mobility).

- Future opportunities for scientific collaborations with Canada include: artificial intelligence, big data and advanced manufacturing.

- As the German and Canadian governments “are on the same track when it comes to science policy, the time is ripe to deepen our collaboration”.

- For more information on funding your research in Germany, visit: www.research-in-germany.org/dms/downloads-en/rig-publications/RiG-Funding-your-research-in-Germany-2016/Funding%20your%20research%202016%20barrierefrei.pdf

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Science Diplomacy

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Maxime Gingras, Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC) and Evidence For Democracy (E4D)

Paul Dufour, Co-chair, Science Integrity Project; Katie Gibbs, Co-Founder, Executive Director, Evidence for Democracy; Matthew MacLeod, RE Group President, Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada; Michael Urminsky, Research Team Lead, PIPSC IPFPC

Moderator: Maxime Gingras, Research Officer, PIPSC

Takeaways and recommendations:

Increasing Canada’s scientific integrity

- Government has to ensure that what it says publicly matches what internal policies communicate to its employees.

- The current environment in the U.S. shows that progress on scientific integrity can be swiftly undone. Canada must ensure that our solutions can be sustained over the long term.

- Scientists need good communications training.

- The media need to know the scientists to call in government departments. Many of these connections were lost in the last 10 years as scientists were less able to speak freely and as many science writers lost their jobs.

- Open data is good but an over-emphasis on researchers having to use Canadian government open licences may be detrimental to collaboration (e.g. if researchers from other countries are being instructed to use their own open data licences).

- Departmental science advisors should have good management skills but they also need to understand science; being a skilled manager doesn’t mean someone is also good at science advice.

Advice for SBDAs developing scientific integrity agreements

- All science-based departments and agencies (SBDAs) staffed by 10 or more scientists have been tasked with developing their own scientific integrity policies. As per the agreement they signed in Spring, PIPSC is endeavoring to work with departments to develop a model policy by the end of the year.

- For policies on scientific integrity to work government must talk to scientists as well as policymakers, and they must take the advice of scientists seriously.

- Policies must include clear guidelines for times of public crisis (e.g. SARS) so that scientists and policymakers respond in a coordinated way.

- Policies must have clear conflict resolution processes and the results of these processes must be made public.

- These processes need to recognize that conflicts require different time frames for resolution. For example, if a scientist wants to present at a conference, a resolution must be found quickly.

- When discussing scientific integrity, the SBDAs should focus on valuing high quality and bias-free work rather than avoiding research misconduct.

The road ahead

- Canada’s new Chief Science Advisor should review and learn from the 1999 report Science Advice for Government Effectiveness and other past work. There is no need to reinvent the wheel.

- Enshrining scientific integrity in government scientists’ collective agreements is a step in the right direction, but the government must champion a culture change within departments that respects, values and understands scientific integrity.

- Groups like PIPSC must continue their advocacy role to ensure scientific integrity remains a government priority.

- The provinces should also think about how scientific integrity affects their decisions and should consider creating agreements with their scientists.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Science integrity

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Milena Raykovska, European Commission, Joint Research Centre

Panelists: Kathryn Graham, Executive Director, Performance Management and Evaluation, Alberta Innovates; Jeremy Kerr, Professor of Biology, University Research Chair in Macroecology and Conservation, University of Ottawa; David Mair, Head of Unit, responsible for Science advice to policy and the Work Programme, European Commission, Joint Research Centre; Bob Walker, Retired Senior Executive, Former President and CEO, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories

Moderator: Monica Gattinger, Director of the Institute for Science, Society and Policy and Associate Professor at the School of Political Studies, University of Ottawa

Takeaways and recommendations:

- As the world becomes smaller and more technology-driven, agreement over facts is becoming more divisive and time horizons are shortening.

- There’s a growing crisis in science triggered by the challenge of reproducing scientific findings and vanity journals. These challenges have been captured by the recently produced Cognitive Bias Codex.

- Scientists are challenged in determining where in the policy cycle to focus, making it difficult to elevate science-based insights onto the political agenda.

- The political ecosystem must be engaged prior to elections as the policy agenda is set the day after the election.

- Work is required by knowledge vendors to change minds with facts in an ethical manner.

- The “Twitterization” of the scientific method has been years in the making but scientists were slow to see it coming. This resulted in policy being influenced more by the ideology and platform of the party in power. The consequences of those decisions can be addressed by the social sciences and humanities.

- The politicization of science can be offset by strengthening the role of Parliament and expanding the role of open science in support of decision-making.

- In a healthy democracy, Science can influence politics by conveying facts and carefully guarding credibility.

- Society invests in the work of scientists who have the responsibility to deliver factual information. Scientists must earn the privilege of being listened to “outside of the ivory tower”

- Scientific consensus and networking are a valuable methods for demonstrating scientific insight but must be aware of the increasing tendency to obfuscate the facts.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Scientists as Conveners

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Stephen Higham, Mitacs

Moderator: Bonnie Schmidt, Member, Science Policy Fellowship Advisory Committee; Founder and President, Let’s Talk Science

Pierre-Olivier Bédard, Canadian Science Policy Fellow, Global Affairs Canada; Kimberly Girling, Canadian Science Policy Fellow, Defence Research and Development Canada; Loren Matheson, Canadian Science Policy Fellow, Canadian Food Inspection Agency; Mahlet N. Mesfin, Deputy Director, Centre for Science Diplomacy, American Association for the Advancement of Science

Takeaways and recommendations:

- Inaugural year of Mitacs’ Canadian Science Policy Fellowship (CSPF) program resulted in some fellows remaining to work at the departments and agencies that hosted them or found employment in other departments or agencies.

- The fellowship program is an excellent opportunity for science-based departments and agencies to benefit from fresh thinking and a new pipeline for employment.

- Fellowships are an important tool for dispelling pre-existing beliefs about how science policy works in government.

- At least one fellow was surprised at how reactive government is, as opposed to acting strategically.

- Fellows benefit from learning on the inside how their government works. For many fellows, the one-year internship is the first desk job they have held, as many come straight from a laboratory environment.

- The CSPF is modelled on the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Policy Fellowship, which places 250-300 fellows annually in the administrative and executive branches of government. The AAAS program has an option for fellows to propose their own work to fill unmet needs.

- The AAAS fellows program has more than 3,000 alumni, creating a powerful informal network that is one or two degrees away from policy development.

- A key role for fellows is to synthesize and reduce meeting proceedings down to one-page briefing notes, developing communications and knowledge translation skills, learning to process information quickly, utilizing critical thinking and judgement, and working under pressure.

- The Mitacs program could benefit from developing a clearer picture of expectations for incoming fellows.

- One agency host said fellows demonstrate a strong desire and willingness to learn and come to appreciate that science policy can work slowly or quickly and has many moving parts.

- One fellow had a long list of ideas of what they wanted to learn but was able to achieve only one or two. The process is much slower than initially thought.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: Lessons from the Inaugural Year

Conference Day: Day 2 – November 2nd 2017

Organized by: Toni Glick, Stella Jiang and Chris Lau | Ontario

Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science

Speakers: Kathleen Kauth, Director of Partnerships, Advanced Energy Centre, MaRS; Irene Sterian, President and CEO, ReMAP; Duncan Stewart, General Manager, Security and disruptive technologies, National Research Council Canada; Michael Tremblay, President and CEO, Invest Ottawa & Bayview Yards; Iliana Oris Valiente, Founder, ColliderX

Moderator: David Ticoll, Director Emeritus, Information Technology Association of Canada

Takeaways and recommendations:

- When attracting big companies to Canada, it is important to also protect the local ecosystem of new venture development.

- This new age of public interest innovation plays to Canada’s strengths:

- Canada is extraordinarily good at R&D;

- Canada has a culture of tackling public problems.

- With the building of a new power infrastructure, the demand for better battery technology will drive accelerated product commercialization.

- The internet solved the problem of transferring information; what the internet did not solve was the transfer of value.

- Blockchain technology is a mechanism for a decentralized protocol that enables the streamlining of several transactions between counterparties.

- Canada can excel in these technology areas:

- New materials: nano-materials, electronics materials and 3D printing – 3D printing can be for a home;

- Optics and photonics: sensors and Lidar technology;

- Renewable energy: energy storage and battery development.

- 3D printing combined with new materials and net-zero homes can be applied to smart cities, as well as smart villages and remote communities.

Documents:

CSPC 2017 Takeaway: When Technologies Meet

Organizer: Global Advantage Consulting Inc.

Speakers: Vivek Goel Vice President, Research and Innovation, University of Toronto; John Knubley, Deputy Minister, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED); Marc LePage, President and CEO, Genome Canada; Avvey Peters, Vice President,

Partnerships, Communitech; Joy Romero, Vice President, Technology & Innovation, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd; Iain Stewart, President, National Research Council (NRC)

Moderator: Dave Watters, President/CEO, Global Advantage Consulting Group Inc.